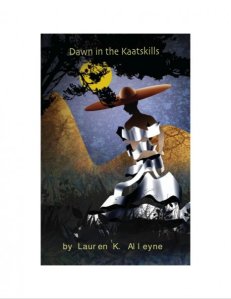

Dawn in the Kaatskills (Longshore Press, 2008)

What’s the oldest piece in your chapbook? Or can you name one poem that catalyzed or inspired the rest of the chapbook? What do you remember about writing it?

“A slow undressing” is the first piece I remember writing in the book. It is the poem that the chapbook takes as its title, but also is the catalyst piece. I remember I had had a conversation with my mother in which she jokingly refered to my father as “rip van winkle” and that sparked my imagination—by default, my mother was his wife, and I couldn’t remember anything about Rip’s wife. So I googled Irving’s story, and read it with a completely new lens – Rip’s wife is HORRIBLY portrayed in the story as a “termagent” “shrew” etc. , even though Rip is characterized as a ne’er do well, her anger at him was the only thing that defined her. I really felt as though she spoke to me, as though this character had been waiting to be seen all these years. And so I wrote the first, and then all the other poems…

What’s your chapbook about? How is it similar to or different from your earlier work?

So the book is in the voice of Dame Van Winkle, and chronicles her relationship with Rip, and how she survives during his absence. There are also overlaps of my poems stemming from my parents’ own relationship that add texture to that story. In many ways, the poems in here are characteristic of my work—I’m concerned with women and women’s voices; I’m intrigued by the constraints and freedom of form; and by stories=– how they’re given to us, how they’re received, who does the telling and what the telling means. My first full collection, Difficult Fruit (Peepal Tree Press, 2014), takes on many of these characteristics.

How did you decide on the length, arrangement, and title of your chapbook?

This actually wasn’t too challenging to organize because it followed the chronology of the story. Inserting the non-Dame pieces was a little bit harder, but really, it was a clear trajectory…

Did you submit your chapbook to contests, open reading periods, or both?

I was approached by a former student, poet Carolyn Whelan, who was completing her MFA, and was taking a publishing class. They had set up presses under the guidance of their professor, Michael Simms of Autumn House Books. She asked if I would be willing to let her publish a selection of poems as a chapbook, and I agreed. It was a limited run of 250 copies, and I thought a great opportunity for these poems to be in the world.

To what degree did you collaborate on the cover image and design of your chapbook?

This image was published on a blog that also featured a poem of mine ages before I even had the manuscript, and I knew then that I wanted it to be the cover of a book. When I had the chapbook published, it was like the dress that had been waiting in the closet for its moment to shine! The artist, David James, kindly agreed to layout the cover for the press, and so my no-so-design-inclined self had little to do with that process.

What have you done to promote and publicize your chapbook?

When the book came out, I read from it everywhere I could. It was, as I said, a limited run, and so mostly I treated it as an opportunity to have a tangible object when I went to readings and the like. I haven’t done much with it in years…

What are you working on now?

I just published my first full-length collection, Difficult Fruit, and I’m mostly getting out there and reading from and promoting that.

What question would you like to ask the next chapbook author featured at Speaking of Marvels?

What inspires you? What gets you to the page?

Have you ever written a fan letter to a writer?

I have been known to slip little fan notes/fan poems into the hands of my poetry crushes. It’s true. I know for sure I gave fanmail/poems to Lucille Clifton, David Mura, and Li Young Lee …

If your chapbook wasn’t a chapbook — if it was in some other form — what would it be?

I’ve often fantasized about this collection as a play or a musical. I just have ZERO skills in that regard! But that would be my choice: I would make this a Broadway musical!

Have you found in your writing of poems that they are separate from you—that they have their own lives and desires—or that they are extensions of you without “selves” apart from your own notion of “self” and your imagination?

My poems behave the way I imagine children behave (or know based on my own behavior as a daughter), which is to say, although they are clearly my creation, they have whole lives and meanings outside of me, and for their sake and mine, I have to give up trying to control those lives and meanings.

Do you think that in the course of your present and/or future career, having written and published a full-length book, you’ll come back to the chapbook, publishing them (or attempting to) as you see fit or as the work seems to elect, or do you see the chapbook as a breakthrough collection to longer works?

I go back and forth. I used to think they were sort of a gateway form, but thinking about it now, I think the microunit of the chapbook is its own legitimate form. None of the poems in my chapbook appear in my collection. This wasn’t always so, as initially I tried to include them, but they were so clearly their own unit, they didn’t play well with other poems, and so I think the chapbook was the form for them. And I think it can be like that. Poems that are thematically or otherwise linked might need their own space, aka the chapbook. That makes me think it’s possible I’ll return to the form.

Concerning voice and style: Do you find it something that you consciously think about or do you simply write? Do try to reinvent yourself every few years, go looking for a new way, or do you think that finding a certain language, a certain voice and pushing and honing it over a lifetime is your preferred mode?

Thinking about voice or style outside of individual poems isn’t really something I do. I let the poems tell me what they want to be and try to honor that as best I can. Because they come from my thinking, feeling, or other internal landscape/experience, I think it’s inevitable that my poems change, but it’s not change I have to go in search of—not if I’m doing my job as a human being in the world, and thinking, living and paying attention!

How do you feel about long poems versus shorter poems? Could a chapbook be a good medium for a long poem?

Absolutely. Think the simultaneous sense of tightness and space in a chapbook is the perfect place for a long poem. It’d be a way to give the poem room to breathe, but be sturdy enough to contain it.

*

Lauren K. Alleyne is the author of Difficult Fruit (Peepal Tree Press, 2014). She holds a Master of Fine Arts degree, and a graduate certificate in Feminist, Gender and Sexuality Studies from Cornell University, and an MA in English and Creative Writing from Iowa State University. Alleyne’s fiction, non-fiction, interviews and poetry have been widely published in journals and anthologies such as Women’s Studies Quarterly, Guernica, The Caribbean Writer, Black Arts Quarterly, The Cimarron Review, Crab Orchard Review, Gathering Ground, and Growing Up Girl, among others. Alleyne is a Cave Canem graduate, and is originally from Trinidad and Tobago

*

*

Happy-Go-Lucky Gone Wrong

My rage: inexhaustible. It consumes –

burns like no other hell, burning, burning,

this middling ground, this limbo, this marriage

of opposing housed in my brittling bones.

He’d return with that gap-toothed grin,

a song souring the air. I’d almost love him.

Then, his arms bare as echoes, whiskey-hot

breath. Then, nothing but his smoky, idle talk:

I am ignited. There is no singing

in me, no sweetly drifting daydreams left

to quench this always-fire in my breast.

I’ve lost my lullabies and love songs to ash,

and she burns, that sugar-tongued woman who

deferred to dream and duty and said, I do.