“To see versions of oneself mirrored and loved in the world is, I think, a human right.”

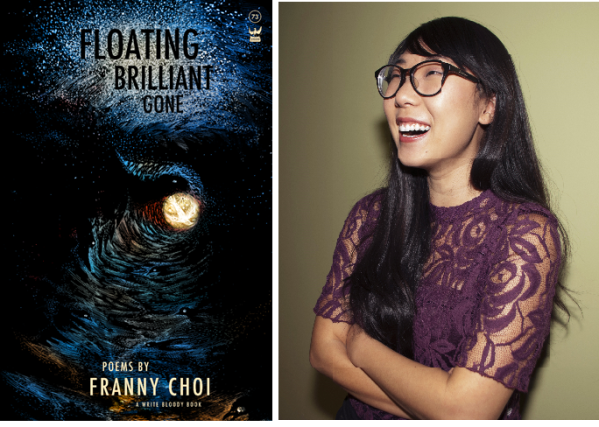

Floating, Brilliant, Gone (Write Bloody Publishing, 2014)

What’s your book about?

My book covers a lot of ground in terms of subject matter – the death of my partner at age 20, identity, resistance, finding new love, spiritual practice, even. At its heart, I think it’s a mapping of the mind as it moves through different kinds of loss. There’s the literal loss of a loved one, but also the small, daily losses of having a body, of being seen, of being marked as different, of trying to love in a world where intimacy seems always to be marked by violence, and ending, ultimately, in the loss of self as a means of escape, or peace, or something like that. The book is examining what is left behind when a something is taken away, and it tries, I think, to use one kind of grief as a blueprint for understanding many others.

What’s the oldest piece in your book? Or can you name one poem that catalyzed or inspired the rest of the book? What do you remember about writing it?

A few poems in my book are version of poems I first started writing in 2008-2009, but they’ve changed so drastically since then that it’s hard to really say if they’re the oldest. “Just Like a Woman,” for example, is one of the oldest poems, but the condensed, semicolon-heavy version in the book was one of the last connecting pieces I added in. However, I do know that the first poem in my book, “Notes on the Existence of Ghosts” is an earlier piece, and it really helped give shape to the rest of the project. I think of that poem as a sort of key for understanding the others; something like a character list, but maybe with emotional states rather than people or images.

Describe your writing practice or process for your book. Do you have a favorite prompt or revision strategy? What is it?

There’s a part of me that’s obsessively methodical, so the first thing I did was to go through every poem that I wouldn’t feel awful about sharing with the world and categorize each one. At the time, I had this enormous pen that could write in like twelve different colors, so I wrote out the title of each poem and color coded them based on theme. From there, I thought of arranging the poems the way I used to arrange mix CDs, looking for the arc that would create the most emotionally satisfying experience for a reader. Once I found that arc, it was easier to see what connective tissue was missing and write into those gaps.

I think writing with the express purpose of fitting a piece into a larger project is a particular kind of writing, and I struggled at times to keep my writing feeling spontaneous and urgent, and not dulled by utility. How do you keep a poem feeling like it’s burst out of its shell, like a spilled confession at 3 in the morning, when you know exactly what you need it to do in relation to the two poems adjacent to it? My answer was to do everything to quiet the more goal-oriented part of my brain, to aggressively seek out the half-conscious state of mind that has always been the most creatively productive place for me to start writing.

How did you decide on the arrangement and title of your book?

The original title of the book was “Familiar Haunt” (70% just for the pun), but my publisher wanted to go with something that better reflected the energy of the book – that whole bursting thing. I made a list of twelve more puns and eventually landed on a line from one of my poems that describes the way a spark moves in the wind; and also, in the larger context of the poem, the way a woman survives being told that her sadness doesn’t make sense. I sort of hated (hate?) that my title has the word “brilliant” in it (like a restaurant that has “delicious” in its name, you know??). But I stuck with it because I realized that this phrase mirrored the structure that was beginning to emerge in the narrative arc of the book: moving from the silence and displacement of an unexpected death, to rage and ecstasy, to deep reflection, and finally, to a shedding of the self. The title gave language to that structure and allowed me to embrace it more fully.

To what degree did you collaborate on the cover image and design of your book?

Jess X. Chen and I have worked together for years (we first met when we were in a Brown/ RISD poetry group together), so we were able to collaborate a lot on both the cover image/design and the illustrations throughout the book. As a poet and visual artist, Jess has a pretty remarkable faculty for closely reading work and reinterpreting it in a visual medium. Essentially, I gave her some parameters and guiding thoughts, she worked up a few sketches, and we went back and forth from there. The birds were her idea, I think, although my poems are probably unintentionally bird-heavy. Oh, well.

What are you working on now?

I’m vaguely working on a chapbook of poems about machine women – androids, cyborgs, me on Twitter, etc. But mostly, I’m just writing – sitting down with myself and seeing what’s there. It goes back to realizing through this project that my best work comes from a need to write the poem itself, rather than planning a larger project. I’m trying to ask what poems I need to write, while being conscious of the connections between those needs. Themes that are emerging are desire, decomposition, post-body love, your average femme sorrows. But I’m trying to take it slow with this next thing.

What advice would you offer to an aspiring author?

To find a community of artistic peers and love each other fiercely.

How has your writing and writing practiced evolved? What old habits have you dropped and are there any new ones you’ve picked up that you’d like to share?

I teach a lot of one-time, generative poetry workshops, and I used to always write along with the prompt while the students were writing. I love having a ten-minute time limit to begin creating something; I think my brain works best when it’s fighting against a restriction. These days, I teach so many workshops that I’ve more often been taking that time to give my brain a few minutes of rest – the value of which I also don’t wish to underemphasize. But I still like writing when it’s hard to write. I bought an old typewriter (like made in the 1930s old!) recently, and some of the keys stick, and the tape doesn’t quite reel right, and roll is cracked so occasionally you tear through the paper; it’s been a wonderfully terrible machine to work with.

What kind of world do you think your book creates? What, or who, inhabits that world?

The world of my book, like many books, is the mind – the paranoid, imperfect, grudge-holding, sometimes-pessimistic, always-joy-seeking mind. It’s the mind confronted by emptiness and trying, often failing, to make sense of its shape.

Did you read straight through your book out loud during the revision process or while finalizing revisions? If so, how was your experience of the poems different? How were your ideas about their individual meanings changed?

I didn’t do that during the writing process, but, as a writer who makes a lot of her living from reading her work out loud, I was always paying attention to sound, even when I didn’t consciously intend it. Recently, however, I made an audiobook version of the book and ended up reading straight through the whole thing out loud at least twice. That was a strange and lovely – and physically draining! – experience. It reaffirmed for me which poems were written to be heard, and which were most comfortable living on the page and had to be shaken out of that comfort zone somehow. There’s one poem written in the form of a flowchart – created with the specific intent of allowing the reader to control the narrative and time. So recording the audio meant that I was forced to dictate those things for the listener, which I sort of hated doing. But I got a lot of help from my younger sibling, Brigid, who is a composer and sound designer and created music for the project, to try to capture something of the poem’s spirit in audio form. I think we did a pretty good job, though imperfection is part of the game in any kind of translation, and especially when moving a text from one medium to the other.

Whose work helped you in the writing of this book?

Sharon Olds taught me so much about writing about grief. Carl Phillips’ sentences. Rachel McKibbens’ fierce engagement with trauma. Most of all, the work of my peers and friends, especially the poets in my collective, Dark Noise.

Who is your intended audience? What kind of person do you imagine writing to?

I’ve found that young Asian American women form a large part of my readership, and I used to worry that this meant that my work didn’t have wide appeal, or that it wasn’t valued by the establishment. If I’d heard someone else saying that, I would have known all the right arguments to make against it, but suddenly, experiencing it for myself, I had a hard time shaking the feeling, or even being able to voice it without feeling some shame. My friend Fatimah Asghar then told me that she wanted to write the book she wished she’d had as a young woman, and that led me to realize (or rather, remember) the value of having an audience that shared these identities with me. The first time I saw an Asian American woman poet read, I was stunned with recognition. To see versions of oneself mirrored and loved in the world is, I think, a human right. I feel immensely lucky that my work has allowed me to be in conversation with many young Asian American women, as well as people who don’t share my race and gender identities. Oh, and lit-nerdy queers, I see you out here, too.

*

Franny Choi is a writer, teaching artist, and the author of Floating, Brilliant, Gone (Write Bloody Publishing, 2014). She has received awards from the Poetry Foundation and the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Poetry Magazine, The Journal, Rattle, Indiana Review, and others. She is a VONA alumna, a Project VOICE teaching artist, and a member of the Dark Noise Collective.

*

*

Notes on the Existence of Ghosts

Leaves stained onto the sidewalk from yesterday’s storm create gray-green watermarks on the pavement, like the negatives of pressed flowers, or the ghost of a letterpress still whispering up from the page. A sidewalk is a haunted thing.

–

I understand the gravity of a train from the empty space and afterbirth air I encounter when I run down to the platform twenty seconds too late. It is the same with all things of such weight – to know them best when you have just missed them.

–

Snow angels; the power of an outline to name an absence holy, a finger pointing to the inherent fiction of angels and therefore haunting.

–

If the stars have, as they say, been dead for millions of years by the time their light reaches us, then it follows that my retinas are a truer thing to call sky.

–

Dove collides into window, leaving a white imprint of its body.

A crime scene outline saying, Take this, the dust of me. Remember the way my body was round and would not move through glass.