“How will we come back to reality as a culture (when the plumbing crumbles? when the moss grows on our evacuated power plants?) or will we never acknowledge how far we’ve strayed from storytelling, from lyric and from truth?”

Apocalypse on the Linoleum (Lily Poetry Review Press, 2023)

What is the focus of your collection?

I collect what Marie Kondo would probably call “sentimental” items: photographs, my children’s artwork, diaries and letters, family lore (scans of original documents, interviews with dead relatives, and summaries in emails), writing prompts, special emails, poetry and photography and children’s picture books (but I’ve been giving away novels left and right), magazine articles, dead plants, and unopened gifts (vases, mugs, leg warmers, scarves, and kitchen gadgets).

What obsessions led you to write your book?

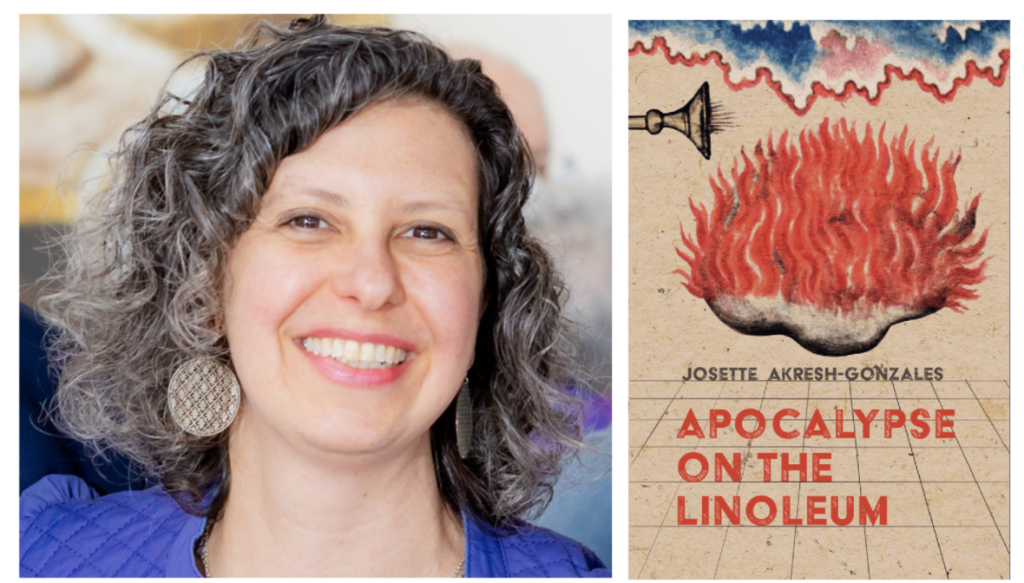

My obsessions are tense and uncomfortable.What ended up as the first part of the book, the section I called “Motherhood in the Anthropocene” is obsessed with the new experiences I had as a mom whose first child had so many questions about the world — religious, environmental, physical, emotional — that I had to find some way to answer. The second part, “Jerusalem,” is a series of poems dealing with both the city and the idea of the city. It’s also informed by my obsession with motherhood — how to be a Jewish mother without burdening my children with something they’d want to run away from. I found it difficult to introduce these poems when they first came out and still do. The following text is from my “author’s statement” pamphlet that I handed out the first time I read these poems to an audience, in 2018:

What’s interesting is that these poems have remained relevant. In them, I was trying only to express my own feelings, memories, and opinions. I was not speaking (could not speak) for anyone else. In 2021 there was a Palestinian protest and retaliation by Israel, and Poets Reading the News took “Unreal,” a poem in this section of my book that’s about my feeling dismayed and speechless because the progressive group I was part of shouted denials of Israel’s existence. And now the poems are relevant again, with the war spiking everyone I know into sharp edges of rhetoric. A call from Verklempt Mag led to them printing “Unreal” in a special issue called “Ein Milim” or “There are No Words.” I always find myself in this uncomfortable, tense place, a member of a tiny group of people working for peace —pacifists — people who can’t side with any group promoting war or violence but side with peace, of feeling the pain of both tragedies.

What’s the oldest poem in your book? What do you remember about writing it?

“Placenta,” which is about the birth of my second child, in 2009, is the oldest poem in my book. Soon after the birth, I wrote the poem for a writing workshop, and started writing poetry again for the first time in nearly 10 years. I remember feeling extremely vulnerable and at the same time powerful. I was compelled to revisit my old, abandoned identity of “poet” by a new friend I’d met at my first child’s preschool — her husband was a poet and had just published a new collection that took several years to write and get picked up. She said, “You should just write — don’t second guess yourself.” And I started to believe that I could do that. A different, online world of publishing had emerged in the 10 years I’d gifted my day job, and it was much less work to send submissions out, get rejected, get accepted, and rinse, wash, repeat. I found it easier to write knowing there would be people reading what I wrote, out there in the world, and “Placenta” started all that — it was published by Two Hawks Quarterly in 2013.

How do you contend with saturation? The day’s news, the disasters, the crazy things, the flagged articles, the flagged books, the poetry tweets, the data the data the data. What’s your strategy to navigate your way home?

Sometimes when I log into Facebook or Instagram or another social site online, mostly to gather events to attend and see pictures of my friends who don’t keep in touch in other ways, I feel so sad, so bereft — what are we trading for this instant exchange? How will we come back to reality as a culture (when the plumbing crumbles? when the moss grows on our evacuated power plants?) or will we never acknowledge how far we’ve strayed from storytelling, from lyric and from truth?

A question from Talia Lakshmi Kolluri: What tools do you use to remain uninhibited in your writing?

I’m uninhibited by nature. In fact, I need tools to remain inhibited! I need to constantly remind myself to cut details that would embarrass myself or my intimate familiars — often it’s the submission process that forces me into this mindset of inhibition.

*

Josette Akresh-Gonzales is the author of Apocalypse on the Linoleum (Lily Poetry Review Press). Her work has been published in The Southern Review, The Indianapolis Review, Atticus Review, JAMA, The Pinch, The Journal, Breakwater Review, PANK, and many other journals. Her poems have been included in the anthology Choice Words (Haymarket) and in Breaking the Glass: A Contemporary Jewish Poetry Anthology (Laurel Review). She co-founded the journal Clarion and was its editor for two years. Josette lives in the Boston area with her husband and two boys and used to ride her bike to work but now works from home for a nonprofit medical publisher.