“In my belly I could feel the formation of a knowing, like a cumulus cloud forms from water vapor….”

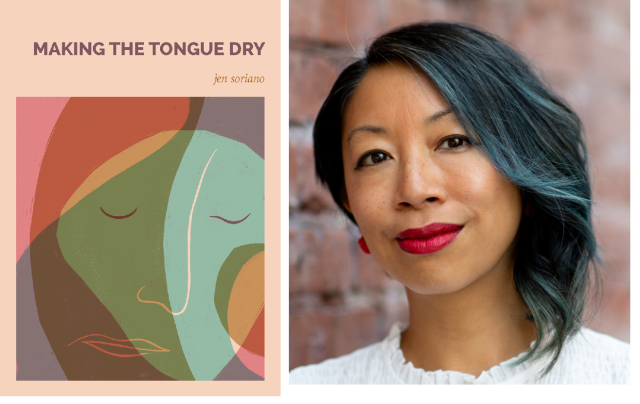

Making the Tongue Dry (The Platform Review Chapbook Series, Arts by the People, 2019, 2nd edition 2020)

order a copy here

Delight Ejiaka: According to your website, you have a background in journalism and communication. How did you go from telling other people’s stories to writing more personal essays?

I believe that all of our stories are connected. Reporting on other people’s stories was a way for me to understand parts of my own story. It was also a way for me to help lift up entire communities who are often marginalized, criminalized or spoken for in mainstream media coverage. I’ve tried to use journalism to help tip the scales toward more just and balanced representations of communities of color.

As far as my journey to writing more personal essays, it’s been a long one! It’s taken me a while to give myself permission to use my own voice. As a woman of color, I get lots of messages from society that my story doesn’t matter, that I shouldn’t take up space for myself, that shining a light on my own experiences is selfish and even narcissistic. I think a lot of women and especially women of color get bombarded with these messages, and sadly sometimes they’re reinforced by our own families, friends and communities. So it’s taken me many years to overcome these internalized messages and to build the confidence I’ve needed to start to share more personal stories.

I’m lucky to be surrounded by a social justice community that has trained me to recognize these messages as lies that uphold systems of racism and sexism. This community has also supported me in spending more time focusing inward. I now see personal essays written by women, trans and nonbinary people of color as feminist exercises and radical acts of love. Sharing our own experiences not only takes courage, it contributes to greater visions of who we can all collectively become.

The opening essay “A Brief History of Her Pain” is very visceral and does not shy away from images of womanhood, menstruation, conception, and childbirth. Why did you choose to write the essay in sections that highlight female pain in different time periods and make it the introduction to your book?

“A Brief History of Her Pain” is an embodied essay and so many of the choices that were made in its writing were made first by my body. The content and the structure of this piece quite literally emerged from my body. My cognitive mind came in later, through revision. After years of laying awake at night wrestling with pain, I began to have thoughts and sensations that told me this pain was not only my own. In my belly I could feel the formation of a knowing, like a cumulus cloud forms from water vapor; the knowing told me that the pain in my body was pain that connected me to many others, and especially to other women who have suffered and continue to suffer disproportionately from unexplained chronic illness.

One night, when my body was twisting and writhing and trembling on its own, I was struck by the realization that in another era, I would have been regarded as possessed. My body told me: you’re a witch! This must have been what many women accused of witchcraft had to feel. So when I began putting words to these experiences, I followed the flow of my body and its sensations and thoughts, and they took me down this path of weaving the present together with different stages of history, to show the endurance of the misdiagnosis of female-bodied and femme-identified pain.

I chose to make this essay the opening of the book because it shows one specific way that history can repeat itself, unless we deliberately intervene in harmful cycles. I hoped it would be an enticing doorway into the chapbook’s unifying theme.

After reading the first essay I wondered why you did not use it for the title of the book. It felt like the emotions that it evoked were so strong and its images were so surprising. What made you decide on Making the Tongue Dry instead?

There was a practical reason for this decision, and also a literary reason. The practical reason is that “A Brief History of Her Pain” was fairly widely read (by my standards!) when it was first published in Waxwing. So if I had titled my chapbook A Brief History of Her Pain, I ran the risk of misleading people into thinking it was just the singular essay repackaged, rather than a collection of essays published as a new chapbook.

The literary reason is that I just like the way Making the Tongue Dry sounds! It has a poetic resonance to me—it’s somewhat mysterious, surprising, and hopefully makes people want to pick up the chapbook to find out more.

Your attention to images, evocative diction, and use of white space seem very lyrical to me. Could you talk a bit about your choice to write nonfiction with a poetic twist?

This gets to another reason that I went beyond journalism to start writing personal essays. I write to get closer to emotional truths that gnaw at me, and that I don’t get to tease out much through everyday conversation. These emotional truths are often complicated, and sometimes ugly, but also often beautiful and deep, and the traditional prose structure of paragraphs and left-margin-justified words on a page can’t always do justice to what needs to be expressed at these deeper levels. I’m no poetry expert but I think that’s why poetry is a literary art that’s so concerned with form. White space, line breaks, prosody and rhythmic syntax all help create an altered experience. Poetic twists can help get to those emotional truths, truths that lie deep but that ironically, when unearthed, help us soar.

The first essay advocates for equality for women and discusses how women were treated like problems whenever they went to hospital, with one doctor calling female patients with fibromyalgia the worst and asking them to go meditate by themselves. The first essay also mentions that women of color are more likely to be undertreated for pain. Later, you introduce new concepts of disconnection, unity, and love. How do these themes connect with inequality and pain? What would you say is the thematic structure of the book?

Erin Jones, the Platform Review editor who chose my chapbook for publication, wrote that my essays urge the reader to sit up and take notice of harmful systems. That is, at core, the purpose of this collection.

Especially now, during the COVID-19 pandemic, when we’re in a moment unlike anything we’ve seen for generations, it’s critical for us to take notice of the systems that have helped save lives and livelihoods, and those that are threatening lives and livelihoods alongside the virus itself.

This chapbook asks readers to look at our own roles in perpetuating or breaking old cycles, and our roles in sowing the seeds of change. At a time of crisis, when a new way of organizing the world seems particularly urgent, these essays bear witness to the impacts of harmful systems while evoking our capacity to persist, resist and transform.

Many essays in your book explore identity and self-realization. In “Unbroken Water” you talk about finding your motherland and people. When I saw the zest with which you devoured stories about your grandfather and how he fought in the war, I thought the stories might be curative or a source of temporary relief. Could you discuss this?

I hope readers find some sense of relief in these stories! I always say my work is not necessarily a beach read—but that I hope they can enjoy it nonetheless.

For me, writing is not necessarily a curative process, which implies a linear progression from harm to cure–it’s a necessary process that I need integrated into my life, like breathing or drinking water. I just don’t feel right when I’m not writing or creating in some way. And when, in that process, I can discover something new—like the fact that my grandfather’s story helped me understand why I myself feel such a martial energy toward justice, or that reflecting on my trip to the Philippines helped me solidify the values with which I do my work toward liberation—the writing ritual becomes elevating as well as sustaining.

I really love the recurring image of water in your book. When there is dryness, there are cracks, and cracks divide the land. Disconnection from your ancestors, the breaking of cities, and the exploitation of the Chico River complicate your image of “the Philippines as a whole singular body… [a] place with intact villages and communities.” How did seeing that brokenness affect your writing?

I think I write because of this brokenness. Most of us have heard that saying, if you can’t find the book you want to read, then write it yourself. I didn’t read a book by a Filipina author until I was in my twenties. I graduated from college without ever having read a single Filipinx author. This isn’t because there aren’t Filipinxs out there writing, it’s because of racism and colonialism. The United States colonized the Philippines for almost 50 years, and still has a strong influence over the Philippines’ culture and economy. The United States has also successfully hidden its imperial past, and part of this has included a systematic marginalization of Filipino-American culture and influence within the United States. Because of colonization, including the 300 years of Spanish colonization that preceded American colonization, the cultural and historical record of Filipinos is fragmented. Our identities and our lands have been pillaged and left torn. Through writing I attempt to assemble some of these pieces, to uplift the power that comes from our endurance, and to celebrate that we can love and accept ourselves even if we aren’t entirely whole.

The mom in “Razing Boys” tries to raise her son by shielding him from other little boys and dressing him with care in a toddler bomber jacket. This makes me wonder about the unresolved trauma of colonization and oppression you have seen. In your experience, are different generations impacted differently? Do the younger generations flee or are they protected from the realities of life by their parents?

Each individual person, each distinct family, and yes I believe each generation, reacts to the legacies of history differently. Right now, I believe we are experiencing a generational thaw. I think for many Filipinx-Americans, because of colonial legacies of violence and displacement, our parents and grandparents had to fight, flee and freeze just to survive. A lot of our elders don’t talk much about the past, and I do believe this has been to shield us, but I also think it’s part of their own coping with unresolved trauma.

Now, I see Filipinx-Americans and Filipinx-Canadians of the Gen X and millennial generations talking openly about intergenerational, transgenerational and historical trauma. Many of us are being more forthcoming about oppression within our own communities, about mental health needs, and about the need to transform colonial mentality and enduring structures of colonization, even as migrant settlers on Native land ourselves. This gives me hope.

The novel coronavirus has thrown so much into question, and too many people are suffering and will continue to suffer from the health and economic impacts of this pandemic. Many Filipinx-Americans are disproportionately impacted because so many of us are frontline health workers, and we are also small business owners and Asian people who have had to bear the brunt of rising anti-Asian racism. So many new traumas are emerging from this moment. But I think we’re better equipped than were generations before us—better equipped with the awareness, language, trauma-informed institutions, and expectations that we deserve the means and the systems to heal. And so even in the face of this crisis, I continue to believe that we are entering a new era of healing from what previous generations had to simply survive.

*

Jen Soriano is a Filipinx-American writer, performer and social justice movement builder originally from Chicago. She writes lyric essays and performance poetry about the intersections of race, gender, trauma, health, colonization, and power. Melissa Febos has called her work “luminous” and chose her essay “Unbroken Water” as winner of the 2019 Penelope C. Niven Prize. Aisha Sabatini-Sloan chose her essay “War-Fire” as winner of the 2019 Fugue Prose Prize, calling her work “vivid” and “cinematic”. Jen is a 2019-2020 Hugo House Fellow and Jack Jones Yi Dae Up Fellow, and received her MFA from the Rainier Writing Workshop. Connect with Jen on instagram at @jensorianowrites.

*

This was a pleasure to write.