“We convince ourselves that all these other things are important–money, politics, our phones, the new TV series. But when birth and death come–when we face important milestones or crises–it’s not these things that we turn to for solace. It’s the natural world, the little things, the people around us.”

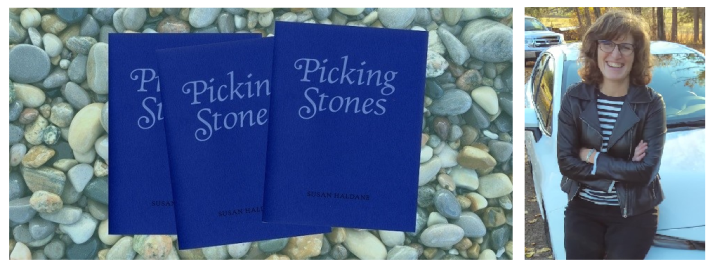

Picking Stones (Gaspereau Press, 2018)

Emma Chase and Kendyl Wadley: I noticed in your blog piece for “My (small press) writing day” that you have “sheep, cattle and in summer a few pigs” on your farm. I did not, however, see any reference to cattle or pigs in Picking Stones, despite the frequent references to sheep. Is there a reason that you wrote as often as you did about sheep? Is there something about them that draws you to them more than the other animals?

I think there’s a practical answer to this question–we have raised sheep on our farm for longer than either cattle or pigs, so I’ve simply had more experience with sheep. But beyond that, the sheep require more hands-on management. We spend more time with the sheep than with the other animals, and we’re more likely to be with them at key moments. I wonder if what draws me is simply the sense of being needed.

Several of your poems (such as “Spring and Everything Turns,” “Instructions for Lambing,” and even “Farm Hands”) explore the idea of new life and new beginnings, while others (namely “Balm of Gilead,” “At the Stockyard,” and “Instructions for Lambing” again) consider the idea of death. How has your proximity to your animals’ seemingly brief cycles of life affected the way you view life and death?

Many of us in North America today are quite isolated from the experience of birth and death. Livestock farming brings those realities into your daily life. You’re forced to find some balance between being overwhelmed and becoming hardened. I think you develop resilience, find ways to take births and deaths in stride, but they still affect you. We still celebrate every birth–albeit in a low-key way–and mourn each death. It would be impossible not to transpose that experience into my personal life. I admit I’m a little obsessed with death, but maybe all poets are. Or all humans?

Jonah’s encounters with the Ninevites, David’s life as a shepherd, and creation are probably the three most prominent biblical references in Picking Stones, and each one casts a fascinating light on their surrounding texts. What inspired you to include these references in your poems?

I grew up in a church-going family. I attended Sunday school and a couple of worship services every Sunday as a kid. I taught Sunday school myself. So these characters and stories are part of my DNA. For me as a writer, and I hope for a reader, these references provide a rich layering like an impasto of colour. I think there’s also maybe some questioning or challenging reflected in some of the mild sarcasm or irony in these poems–I think part of our job as poets is to challenge truths and traditions.

There seems to be a strong tension between the advancement of progress described in some of your poems and the almost stuck-in-time nature of rural life described in others. For example, the description of the rural landscape “[g]one / to concrete, gone to steel, gone / for streets, strip malls and houses, / houses, houses” in “Aerial Photographs” contrasts with the description of how a farmer’s life is unchanging––“We have been here forever; we will be here / forever waiting on the land / while the sun shines”––in “Making Hay” and other poems. How would you describe the way you feel this tension as a farmer and writer?

All the farmers I know are very much interested in new approaches, new technology, best practices. In contrast to that, though, we are working with (or against) elemental forces, and the work of raising food is so fundamental that it carries a huge weight of tradition. I think farming honours the generations of labourers who’ve come before, and I hope to do the same through my poems. But let’s face it, farming is under-appreciated in our urban society. People believe their food comes from Walmart, and land is valued much more as real estate than as garden and food source. When I have to go to the city, I find the urban sprawl thoroughly disheartening. We just can’t seem to stop ourselves. Does this sound like a rant?

One aspect of your poetry that I found highly moving was its descriptions of nature, especially those parts which so often go unnoticed. The chapbook’s evaluation of stones as pieces of pieces of “Creation” with unknowable histories (“Picking Stones”) and its vivid details in “Spring and Everything Turns” are two of my favorite examples of these descriptions. The poem “Starling Ballet” gives some insight into how to go about appreciating nature with its declarations of “to hell / with science! And the damned inquiring mind” and “For once can we just / look.” Could you comment on your process for writing these descriptions and examining the world around you?

It’s another paradox of farm life that you’re surrounded by nature, but so often nature just looks like more work! Still, I feel incredibly fortunate and blessed to live in a place and in a way that’s so close to the pulse of the seasons, to the flora and fauna. I make a point of stopping to notice which wildflowers are in bloom, which birds have come back to the pasture, the way the snow drifts have scrolled around the fence posts. I think the reference to the “inquiring mind” in Starling Ballet is a note-to-self to remember to stop, observe, appreciate, breathe. It’s a reminder that I don’t always have to name, understand, and explain things.

Two of your poems, “Instructions for Lambing” and “How to Shear Sheep,” are written in the second person and resemble how-to instructions in a way that causes the reader to insert him- or herself into the drama of the poem. What was the motivation behind choosing this mode of writing?

Especially with “Instructions,” the how-to approach was a way for me to gain some distance from an emotional event. A writer named Nicole Breit talks about finding a “side door” into difficult material. The how-to was my side door.

In “Current,” you write about a group of boys who link hands and touch an electric fence. What inspired this poem? Is there some kind of story behind the boy named Charlie (perhaps a regretted personal experience or something you witnessed)?

Everyone on a livestock farm has accidentally touched an electric fence–not a pleasant experience. Charlie is a real kid, a friend of my son, and the poem came from a real event, when a bunch of the boys did exactly this. The kid touching the fence then doesn’t receive the shock, but the last one in the line gets a reduced jolt. I don’t know why they decided to do this–must be a boy thing…

I noticed that three different poems, “Balm of Gilead,” “Starling Ballet,” and “Villanella Borealis,” contain references to stars. Are you partial to the night sky or astronomy? What do you think it is that draws your attention to it?

We can see the stars here. We’re so lucky! It’s hard for me to conceive that there are people who rarely get to see the constellations. I am in love with the night sky for all the clichéd reasons – so vast, so distant, so eternal… Again, my natural inclination is to name and understand and explain. My grasp of astrophysics is pretty rudimentary, but I do find it fascinating. I think it’s an area where science and religion don’t need to be mutually exclusive. The more we learn about cosmology, the more it suggests, to me, a brilliant creative force behind it all.

In “Spring and Everything Turns,” you vividly describe the change of the seasons from winter to spring. Which season would you say is your favorite to behold? Which season is your favorite to write about?

Spring is hard to resist–there’s nothing sweeter than baby animals and few things more rewarding than helping a newborn lamb or calf find its first sip of milk. But fall is likely my favourite season. I really appreciate the slowing pace of things after the hustle and heat of summer. I find myself writing often about November, which is probably the least obvious month if you were looking for poetic inspiration!

“Picking Stones” for a farmer refers to his/her responsibility of removing stones in order for new crops to come to life. It is the tedious and necessary task that no one is ever eager to do, but if it’s avoided, growth is stunted. In what ways does your title and this reference relate to what is required of life?

It’s true; there are many tasks in farming that are tedious and necessary! It’s a pretty boring philosophy of life, but I do believe in the value of showing up every day, doing the hard stuff. I don’t necessarily expect that hard work will be rewarded in any tangible way, but there are intrinsic rewards. “We choose to do these things not because they are easy but because they are hard.”

Throughout your chapbook, there is an emphasis on creation and the importance of acknowledging the world around us. For example, you open the chapbook with “we stub our toes on creation.” In “El Camino Trail,” you say, “It’s important to notice the little things.” Why is it important for you and your readers to be grounded in creation? How has raising sheep allowed you to do this, and in what ways does creation validate your faith?

And really, what else is there, but creation and the world around us? We convince ourselves that all these other things are important–money, politics, our phones, the new TV series. But when birth and death come–when we face important milestones or crises–it’s not these things that we turn to for solace. It’s the natural world, the little things, the people around us. My faith is pretty simple, too–it’s very much based on caring for creation and caring for one another. On our farm we do our best to mimic the patterns and preferences that our animals have naturally. So raising sheep has allowed me to fulfill a call to stewardship.

I love the language in all of these poems, especially in “At the Stockyards”: “To the air: Always this gift—from sawdust hushing under the lambs’ hooves on the ramps and away down the alleys, the scent of beginnings until just now forgotten.” I found it the most challenging piece to read. The chapbook seems to focus on creation, life, and hardship. How does “At the Stockyards” fit in with these overall themes?

You asked earlier about a favourite poem or one that was difficult to write. It’s interesting that you found this one challenging to read, because it was likely the most challenging to write. I’m committed to livestock agriculture, our role in caring for creation, and the part livestock farming plays in mitigating climate change. But when the time comes to say goodbye to our animals, I’m always torn. I’d been wanting to write about this for a long time but couldn’t find a way in. Finally I realized I needed to just capture some of the physical surroundings and write the experience in a minimalist way.

The last poem, “Current,” says, “The pacemaker in the barn ticks and the charge circulates, travelling its marathon patrol over the esker, through the creek’s floodplain, along the forest hem and finally home.” I appreciated that there was a resolution to the journey that this chapbook follows. What does returning home and this finality signify?

I’m not sure it’s resolution so much as resumption. Farming, of course, is a cycle as is the electricity that flows through the fence. For me the idea of home is at the centre of those cycles.

You’ve written, “Most of my writing happens in my head… I repeat and repeat a line or phrase in my head until I have a chance to write it down… I trust that it will still make sense when I come back to it later.” Other than this, how do you approach the writing process?

I try to take time to write every day, but I miss a lot of days! When I do have time, it may be 15 or 30 minutes. I usually read a bit of poetry to focus and quiet my brain, then write. I do a lot of revision. My first couple of drafts are handwritten–that feels more creative for me than drafting on screen. I’ll write and rewrite, then eventually type it up and leave the poem to ripen for a few days or weeks (or months) before I come back to it to try to read it with fresh eyes.

Do you have any advice for emerging writers who are also trying to write or publish a chapbook? What advantages or disadvantages do you find in putting together a chapbook versus other types of publication?

A chapbook is a lovely compromise–long enough to allow you to develop a focused theme but short enough to be within reach. I don’t feel qualified to offer advice, but things I’ve learned as I go would be to prune aggressively, revise repeatedly, proofread diligently, and detach from the brilliance of your first inspiration. And then at some point, you just have to decide it’s done and send it out there and try to get on with the rest of your life.

*

Susan Haldane is a poet and works for a social services charity. She farms with her husband on the edge of Northern Ontario, Canada. Her work has been published in a number of literary journals in Canada, and in the anthology “Desperately Seeking Susans” from Oolichan books. In 2019 she won the Magpie Poetry Prize from Pulp Literature. Her chapbook “Picking Stones” is published by Gaspereau Press in Nova Scotia, Canada.