“Perhaps the biggest challenge to continuing to write is realizing you are the only person who deeply cares if you keep writing.”

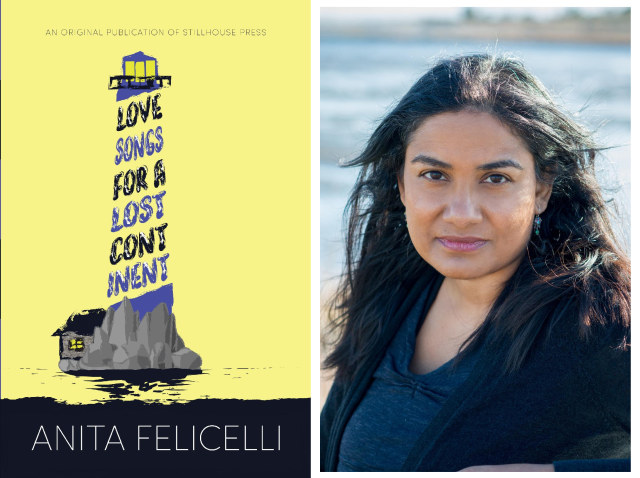

Love Songs for a Lost Continent (Stillhouse Press, 2018)

Of the stories in this book, do you have a favorite?

I’m not someone who claims not to have favorites – of course I have them. I have three favorites: the title story, “Once Upon a Great Red Island,” and “Rampion.” The first because it allowed me to write about language and identity, which are an endless source of interest to me. I love “Once Upon a Great Red Island” because I’m interested in the rifts between people, people from the same and people from different cultural backgrounds, and all we’re unable to adequately communicate with each other (and more idiosyncratically, this story distills certain plot points of an earlier failed novel, and it allowed me to salvage what I found beautiful from that failure). “Rampion” I love because it’s absolutely, purely my own aesthetic that I didn’t need to change at all in order to publish – surrealism and my favorite childhood fairytale and deep tragedy all rolled together.

In your interview with Sarah Luria for Medium, you explain that some of your stories “grew out of an autobiographical seed.” Could you say more about this?

I pay close attention — often painfully close attention — to what’s around me. I’m often inspired by something I’ve witnessed, even if that’s only a sensory impression. Nothing I’ve put into the world as fiction so far could be fairly construed as autobiography, but at least one aspect of every short story grew out of something I’ve experienced, but imaginatively transformed. For example, I did visit Madagascar like my protagonist does in “Once Upon a Great Red Island,” and I’ve worked with finance guys. However, my travels weren’t linked to a vanilla farm, nor have I dated a hedge fund manager like Leon, as my character Tarini does in that story.

Your characters are fascinating and dynamic, and their pursuits of what they desire can twist your stories in interesting ways. Do you have a favorite character in Love Songs for a Lost Continent? Which characters are most like you personally? Are there any characters you particularly dislike or struggled to write?

I most love Hema in “Hema and Kathy.” She’s vibrant and spirited, and when she makes a decision that might be a mistake, that everyone around her recognizes as a terrible mistake, she still goes full-force into that decision. She follows her heart even when her heart makes her an idiot. There’s something tragic and vulnerable in that, and yet also honorable. How many people truly follow their hearts? The older I get, the more I understand how rare that is, how often we contort what we truly want in order to better fit with what we think we want, or even more often, what society thinks we should want. I love Hema’s chutzpah, her unwillingness to let herself be defined by her upbringing, or the worldview her parents want her to have.

I share certain, strangely opposite personality traits with both Komakal in the title story and Leda in “Swans and Other Lies.” Komakal’s an artist; she’s passionate to such an extreme degree, it’s hard for her to be among other people who care less. Leda in “Swans and Other Lies” is a shapeshifter without a sturdy identity. She’s able to mold herself to what a situation requires, and inclined to keep her feelings to herself.

I had a little bit of discomfort with the character Devi in the story “Snow” and the character Maisie in “The Art of Losing,” but I’ve spent so much time with them, dislike doesn’t enter the equation. It did feel unfamiliar and challenging to put myself inside worldviews so different from my own, and to depict them in a way that I think is honest, rather than either sensationalistic or falsely conciliatory.

I imagine that a book like yours required grit and vulnerability, that you poured yourself into these stories. At what point did you know that you wanted to be a writer? Were you challenged in your pursuit of that dream and desire?

Thank you for saying so. I did pour myself into these stories. I knew I wanted to be a writer at age five. I wasn’t as challenged as some writers in pursuing that dream because I developed a writing habit so young it wouldn’t occur to me not to write. I assume it’s more challenging to come to writing in middle age and develop a habit. I’ve never stopped writing, even when I had a day job that drained me emotionally and made my writing stiff and ugly, and I’m fairly certain that’s because I see writing as part of my identity, a bigger part of who I am than my cultural background or my gender. Perhaps the biggest challenge to continuing to write is realizing you are the only person who deeply cares if you keep writing.

Are there any short story authors that have impacted your writing, or any you enjoy and would recommend?

Early on in my writing life, I read Isaac Bashevis Singer, Flannery O’Connor, Franz Kafka, and Nikolai Gogol, and these authors almost certainly impacted how I write. Short story writers I love and recommend: Joy Williams, Robert Coover, Ben Marcus, Charles Yu, James Baldwin, Kelly Link, Denis Johnson, Laura van den Berg, Kelly Luce, Rajesh Parameswaran, Nina McConigley, Jamel Brinkley, Kali Fajardo-Anstine, and Rita Bullwinkel.

How long did it take you to write Love Songs for a Lost Continent? Could you describe your writing process with this book?

I wrote one of the stories in the collection, “Wild Things,” back in 1998 in a writing workshop. The others were written in the interim. In 2014, I noticed there were certain recurring themes in my stories — memory, identity, and reinvention. I started looking at how the stories with these themes might fit together, even if some had a surrealist bent, while others were odd in their observations, but could still fit within the realm of realism.

In your interview with Drunk on Ink’s Soniah Kamal, you mentioned the pain of rejection in the writing and publishing process. How did you push through to get your stories published? What advice would you give to fellow writers who are stuck on their third or fourth rejection letter?

Rejection is a constant of writing (and other arts) in a way that it is not in other vocations. Paraphrasing and interpreting Toni Morrison, you have to treat rejection with dispassion, as information about a particular reader’s affinity for your material, and tolerate the ambiguity of that. Unlike a law firm or corporate job, rejection in the arts might mean you’re doing something relatively new, or something editors don’t know how to read yet. Our lives are set up to favor those things that are clear, easily classified, and that conform to the existing structures and thinkers of the society in which we live. But brilliant writing may not conform the way other endeavors do. The only good reason to write is because it gives you something other endeavors don’t, and so you learn to keep going simply through the act of keeping on keeping on.

In your experience, what is the role of emotion in writing? How do you see emotions at work in your own fiction?

The role of emotion in fiction varies depending on the story being told. Some stories mandate a hotter emotional temperature than others. As a reader, I privately note when a story makes me feel I’m being manipulated with a false or unearned sense of tragedy, and I hold that author’s work at arm’s length ever after, even if I like the style and subject. Being hit over the head with emotionality in writing tells me an author doesn’t trust me, and therefore might not be entirely trustworthy either. With every piece of fiction I write, I’m conscious of tailoring the degree of emotion revealed based on the personality of the main character. I read to be inside someone else, not necessarily or always to feel all the feels, so I want to transport the reader into a particular protagonist’s headspace, particularly when I’m writing in first person or close third. Sometimes restraint and allowing a reader to come to the emotions or even work towards emotions, rather than dragging him or her there, is a more inviting approach.

I used a cooler approach in “Love Songs” because of its first person narrator’s personality. The story centers a man caught between different worlds — the two different worlds of his parents’ different caste identities and the different worlds of South India and America. He has a hard time feeling anything, and part of that is his personality — cerebral, intellectual, analytical — but the other part is that he has to code-switch and recalibrate all the time due to traveling in between worlds, and that consumes so much mental space, he doesn’t have time to pay close attention to his emotions. The unnamed narrator in “Rampion” is much more attentive to her emotions, and her grief and anger drive her to do a terrible thing. In my novel, Chimerica, the narrator, Maya, is a trial attorney who mostly suppresses her emotions in all her interactions. Trials are battles, are violence, and attorneys absorb the violence for their clients, and so Maya, like other attorneys, usually doesn’t make herself vulnerable by showing her real feelings to the other characters — everything needs to be about performance, rather than authenticity.

In the beginning of “Elephants in the Pink City,” Kai and his father bicker over anything and everything. However, by the end of the story, their relationship changes. Could you talk a bit about your interest in changing relationships?

I’m fascinated by the moments that transform people. But, unlike some other writers, perhaps, I don’t see any individual as operating in a vacuum. We are made out of our relationships to other people, of how other people see us and treat us, our collective memories, our personal and cultural histories. Kai has a fraught relationship with his parents, especially his father. They don’t understand and support his decisions, not only because he’s gay and they’re socially conservative immigrants, but also because he’s American. His father is simply unable to make the imaginative leap necessary to understand him. Sometimes what feels uncanniest in the Freudian sense is someone or something that looks similar to something you can identify, and yet is somehow slightly different. It’s unnerving when a similarity or resemblance is clear, and yet there’s a difference. Kai is making decisions his parents can’t identify with even though he looks like a Tamil person, like them. So, it’s Kai who needs to undergo an experience and through that experience, understand this gap between himself and his father. He needs to reconcile himself to a basic irreconcilability in the relationship, to the possibility love might transcend the distance in experiences, the blindness we have to each other’s experiences.

I’m fascinated by how the most transformative moments of our lives are often the ones that involve how we see another person or how they see us. Playing with the opening and narrowing of the many gaps and fissures between people is so interesting. How do we stand in right relationship to one another when change is constant? I’ll likely be wondering and writing about this for the rest of my life.

∗

Anita Felicelli is the author of Chimerica (WTAW Press) and Love Songs for a Lost Continent (Stillhouse Press). Her essays and criticism have appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle, Los Angeles Review of Books, Slate, Salon, the New York Times (Modern Love) and elsewhere.