“Creativity stems from the flux of something in the middle between the input and the output. Once you reside in the middle of that, focus on what you want, and own it. It’s yours.”

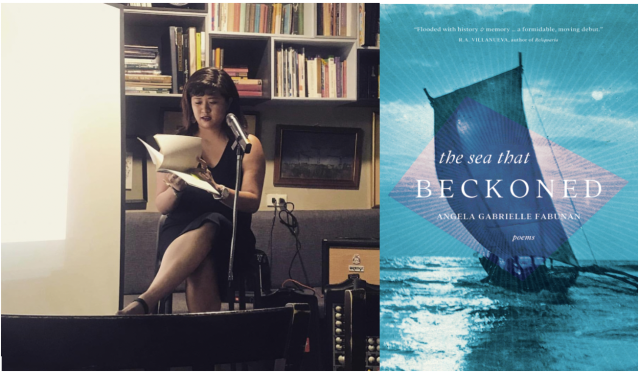

The Sea That Beckoned (Platypus Press, 2019)

The opening poem, “First Day,” suggests fear and hope and loneliness, which seem to be recurring themes in the book. Could you say a bit about your choice to start with this poem?

I start with this poem because it is a good starting point which the rest of the collection jumps into, namely belonging and what I call the state of unbelonging. “First Day” makes the decision of the speaker to the highlight the fear, the hope, and the loneliness of this state of unbelonging quite apparent. While there is fear and loneliness in unbelonging, which is at first the emotions of the speaker, there is also hope in finding a community where one isn’t fearful, where one truly belongs.

You place Filipino/Tagalog words so that English-only speakers will understand the poems from context. Could you talk about how your poems play with languages and what some desired effects might be?

I was aware of the choice I was making in code-switching from Tagalog to English and English to Tagalog. Although I am not as skilled in it as others who write bilingual or multilingual poetry, I wanted to make clear the language barriers I experienced in moving back and forth from America and the Philippines. I wanted to simulate an experience that would make the text unfamiliar and yet familiar, but I also didn’t want to be incomprehensible at the same time. That’s why my publishers and I decided not to include a translation page; we thought the code-switching, though not seamless, was fitting for the work as a whole.

Could you discuss “Vacating”? Its metaphors suggest a summer romance—different in tone and subject from other poems in the collection. What made you decide to include it?

I included “Vacating” almost instinctively, because it was one of the first poems that I wrote about my childhood town of Olongapo City, Subic Bay, and Zambales, Philippines. I thought it fit because the overwhelming metaphor of the sea is there. It’s one of the earlier poems because, later in the collection, I destroy that innocent summer romance when the rainy season comes, or maybe it destroys itself. But I definitely wanted to include that sweetness of that poem in this collection, that excitement of being in love and wanting to linger in that moment, which is why I suppose it has a different tone, because the narrative sort of goes downhill from there. What happened to that summer romance? Well, it started raining.

The different concepts I introduced in that poem expanded to become the subject of other poems in that collection in my writing process from 2014-2017: the semblance of being midway from the beginning to end, the momentary glimmers of a good love, arrival and departure, belonging and unbelonging, memory, the shore, the sun—all of these elements make their way through the rest of the chapbook, though maybe not quite in the same cheery tone.

Your biography says that you were born in the Philippines and raised in New York City. Have you traveled to the Philippines, and how has that influenced your writing?

I currently live in the Philippines at the moment and I’ve been here since 2012. I was born in the Philippines and migrated to New York at an early age in 1997. Before I went back again in 2012, I had only visited once or twice. So, in the early stages of my writing life, Filipino writers and books did not influence my writing as much as Anglo-American literature did. I remember one specific moment when I was at my favorite library in New York trying to find the Philippine Literature section of the library. They said it was on the third floor, but I didn’t find anything and went home empty-handed. That was a sad moment. I suppose that’s why I write about the Philippines now, because I’m still trying to make up for that one sad moment out of all the sad moments of my life.

When did you decide that you wanted to write, specifically poems about your heritage and history?

I didn’t know much about Philippine heritage and history before I went back to the nation as an adult, so I felt unqualified to write about it before then. I still feel that way now, and I think my work is less in the category of Philippine literature than it is Filipino-American literature, which are two different things. When I started learning a little about the very dramatic history of Philippine Literature in English, including the works and the lives of the authors, I was intrigued. I thought it would be at the very least interesting to talk about Philippine diaspora, but I guess I didn’t realize its importance to the many people who have had that experience, until people (of all backgrounds, not just Filipinos) started telling me about their own experiences of migration, after reading the book. In this always-connected world, our times breed ambivalence about our own histories and heritages amongst the histories and heritages of those we encounter in our daily lives, no matter what country we live in. And, The Sea That Beckoned wants to scratch the surface of that ambivalence.

The acknowledgements mention teachers, classmates, family, and friends who built you up as you developed this book. Were there times you experienced setbacks, and what advice would you give to aspiring writers who are discouraged?

The people I’ve mentioned in my acknowledgements are only a small list of people who have contributed to the book. There are many more that should be credited for their help in developing my work, but I hope that there will be more books to come for that. This is because nearly every conversation I have had with every person I have met in my life has contributed in some way to my writing. Sometimes, even those conversations I have accidentally overheard have contributed.

There were definitely many times I experienced setbacks, hundreds of setbacks. For example, I have applied 121 times since 2013 to now to publications through Submittable, and I have been accepted 7 times. That’s not including the email submissions or query letters I’ve sent. Being a writer is not an idyllic day job; a writer falls many times before they can even contemplate walking. So, my advice is to keep walking, with your head held high. There is no one that can tell you if your writing is good or bad but yourself. You are your own best friend and worst enemy, as well as your friendliest and stiffest competition. And allow yourself to take some time off to take care of yourself. Use those times to read in order to further your craft. Read everything; menus, manuals, poetry, stories, news sources, your lover’s eyes, your mother’s hands. Reading these will all teach you something that can help you in your way. Creativity stems from the flux of something in the middle between the input and the output. Once you reside in the middle of that, focus on what you want, and own it. It’s yours.

Oh, and my advice to young writers is read, write, and get accustomed to being poor.

Which poem in your book has the most meaningful back story? What’s the back story?

They all have back stories, some which I’m willing to reveal and some which will remain private.

Most of the poems were written between 2014-2017 in and out of workshop classes in the master’s program at the University of the Philippines. This was around the time I felt that bit of unbelonging and I was still adjusting to the new school environment. The Filipino-American label came to be prominent around that time, but it was less of a self-identification and more of a marker that explained why I talked and acted the way that I did. It was a label people automatically placed on me. I eventually have come to love and embrace being a Fil-Am, but it was something to be accustomed to—it was a foreign concept to me at first. I think that state of being neither American nor Filipino as well as being both has grown into this collection. That’s pretty much the backbone of “Midway” or “First Day.” “First Day” was written in the Philippines, about my experience entering classrooms and being weird about my Fil-Amness. “Midway” was written in NYC when I was working full-time in the Flatiron District, about how being in that space and missing home was weird as well.

Which poem is the “misfit” in your collection and why?

They’re all somewhat misfits that somehow make up my misfit life. Half kidding. On a serious note, though, there’s an overwhelming narrative of the “misfit.” To answer your question, I think “To The Man Who Claimed Me” was a difficult poem to conceive, to write, and to edit. I wanted to make an homage to a great Filipina poet, Angela Manalang Gloria, and wanted it to coincide with her famous sonnet, “To The Man I Married.” I’m not convinced that I did her justice in my rip-off, but I tried my best in the editing rounds, along with my publishers Michelle Tudor and Peter Barnfather, to convey the right emotion and message. It doesn’t quite fit in with the rest of the poems because from a readerly lens, I think it’s too romantic, and as a writer, I think it’s thoroughly unfinished (although I subscribe to the belief that all poems are unfinished, to a certain extent). So, I’ll be working and revisiting that poem in particular in my future practice.

Did you have any rituals while writing these poems? What were you listening to when you wrote them?

Sometimes, when I commit myself to locking myself inside my apartment and writing, I put scented oils in a burner and get so sleepy that I don’t actually write. I can’t write on my bed, I can’t write while on moving vehicles, I can’t write in complete silence. I can’t actively listen to music while writing, although white noise, some chatter, and some overhead music is fine. This is why I write on a chair, in the upright position, usually in a café where there’s background noise and refills of coffee.

What was the final poem you wrote or significantly revised for the book, and how did that affect your sense that the book was complete?

The poem towards the end of the process that I and my publishers made extensive edits to was “Fishnet,” which appears in the first half of the book. We decided collectively to condense two poems into one and then edit that version. “Fishnet” combined some aspects of part II of another poem, “Fair Game” published in Maganda Magazine, USA. I think it’s fitting that editing “Fishnet” was one of the last things I did, because it’s literally about beckoning and fantasy production. I think the book tries to beckon its readers into an experience of a fantasy as much as that of realistic social conditions. So, whenever someone picks up my book, they’re in my fishnet.

*

Angela Gabrielle Fabunan was raised in NYC and lives in the Philippines. She graduated from Bowdoin College and attends the University of the Philippines MA Creative Writing Program. In 2016, she was awarded the Carlos Palanca Memorial Foundation Awards for Poetry. She has been a recipient of the Rutan Grant as well as the Gibbons Fellowship, and participated in the Silliman University National Writers Workshop. She is a poetry editor at Inklette Magazine. Her first book of poetry, The Sea That Beckoned, is available from Platypus Press.

Link to her online portfolio:

agfabunan.journoportfolio.com/publications

And some poems she is personally proud of:

http://cordite.org.au/poetry/notheme8/call-of-summer/

https://www.haranapoetry.com/i19-midway

https://www.asymptotejournal.com/special-feature/angela-gabrielle-fabunan-homecoming-of-age/

https://www.asiancha.com/content/view/1933/476/