“I’m almost always writing about characters struggling to understand the world around them, people reaching for connections and thwarting them simultaneously, people who don’t always admit to wanting to be heard, seen, found.”

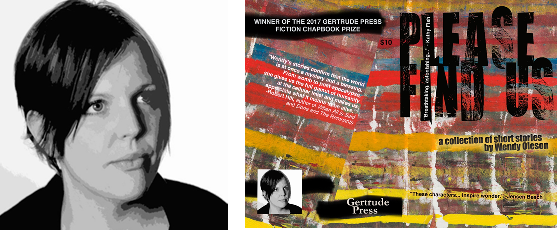

Please Find Us (Gertrude Press, 2018)

Please Find Us is your second chapbook. What continues to draw you to this medium?

First, thank you so much for reading my chapbook and taking the time to ask such thoughtful questions!

Presses and authors don’t publish chapbooks to make money; it’s a labor of love. This means, among other things, that there’s more room to experiment. I’ve also noticed that short story collections almost always shift gears thematically and tonally; chapbooks don’t necessarily have to.

Which piece of writing that you have written is your favorite?

That’s such a good and hard question. In my mind, “favorite” quickly translates to “most proud of” and that often means “the piece I struggled with most.” There’s a story I’ve been working on since 2005, and if it ever sees the printed page, it’ll be my favorite. But I’m also really fond of a dog character in another unpublished story—the dog came about organically but is ultimately so necessary to the story. And I’m goofy for dogs.

What other writers inspire your work the most? What works of literature are your favorites?

I’m thrilled by the passionate readership Carmen Maria Machado found through Her Body and Other Parties. Recently, I’ve really enjoyed Nick White’s story collection, Sweet and Low, and his debut novel, How to Survive a Summer. Joy Williams, Lorrie Moore, and Roxane Gay all make me want to keep writing, and when it comes to chapbooks, Split Lip Press, Black Lawrence Press, and Rose Metal Press publish consistently stellar work. Of course, I’m also partial to Gertrude Press!

Many of the stories in Please Find Us deal with difficult topics, such as death, grief, suicide, abduction, and broken families. Many of these stories center around young protagonists. “The Snow Children” stands out in particular. In this story, Sarah becomes increasingly isolated, as she grieves the death of one of her classmates. Could you discuss the juxtaposition between adult topics and child protagonists in this chapbook and elaborate on how this device works in “The Snow Children”?

The idea that some topics belong to the realm of adults makes so much sense on the surface, but it quickly breaks down in light of children like Sarah who find themselves in essentially incomprehensibly-horrific situations. Adult brains should be more capable of understanding death than the developing brains of children and adolescents, yet the grieving process often goes haywire—even for adults. In Sarah’s case, she’s having trouble understanding how she should think, feel, and behave, but she’s also acutely aware that the adults around her aren’t doing such a great job either. When reality and the natural world fail to provide answers, she’s forced to look elsewhere.

“Suffocate” uses various contrasting images of oil to tell a story about unfulfilled dreams. How did oil develop as a recurring image?

I don’t always write this way, but the image/sensation of oil was the engine of the story. This idea of a spreading, unwelcome oil and it being a problem: that’s where it began. Now it makes me wonder whether I’d recently seen footage of crews cleaning wildlife after an oil spill—that delicate sudsing of birds.

The theme of dysfunctional relationships is present in several stories in this collection: “Little House, 1979,” “The Snow Children,” “Sister,” “Brother,” “The Milky Way,” “Where Sleep Hides,” and “Record from a Farmhouse.” The imperfections of these characters make them seem more realistic. What do you think about when developing characters?

I have to be patient. The significant details that help compose characters in my work usually don’t come all at once. It’s a slow process of discovery and paying close attention to their sensory experiences. I truly delight in imperfections despite my perfectionist tendencies. Or maybe they go hand-in-hand, knowing perfectionism in myself is dangerous and counter-productive and delighting in the imperfections of others?

Tell us about your writing routine. When do you write? What does your writing space look like?

Two beverages, that’s the constant: a glass of water and a mug of coffee or tea, or water plus a mason jar of iced coffee with almond milk. Or water and seltzer water. I’m a thirsty person. My brain takes a while to turn on in the morning—or maybe I just tell myself that—so I tend to write in the evening instead of early mornings. I envy those people with the gumption to get up at 4:30 a.m. in order to write. Those people deserve all the glory.

In “Sister,” details such as the “cat’s cradle of scars” on the narrator’s hip and the “six-chambered fury” of a heart allude to the idea that the sisters were born as conjoined twins. In “Brother,” the imagery is reminiscent of Hansel and Gretel, where the siblings could not survive without working together. Both of these stories allude to the idea that the narrator needs her sibling to live. Were they meant to be read as a pair?

Yes and no. Yes, because I did love the idea of this pair of super-short flashes playing off of one another. No, because I also regret that it would be so tempting to read them as connected in terms of assuming character overlap. I worry the pairing then becomes a bit confusing (I’ve been told by a family member or two that my work can be unnecessarily confusing). I certainly don’t aim to confound!

The pieces in this chapbook address a diverse array of topics and are told in a variety of tones. How did you decide on the order for Please Find Us?

I honestly go by gut feeling—what I think should come after what, and so on. It’s an imperfect arrangement, I’m sure, but it felt right to me. In the past, however, I’ve taken other approaches. For example, when I was trying to figure out how to order a full-length manuscript of short and short-short stories, I got out scissors and markers and tried to create a color-coded index card for every piece. This quickly became complicated because I was coding and labeling them based on narrator/POV/tone/theme, and I was taping/removing/re-taping them onto a dollar-store cookie sheet in order to “see” how the collection might work. The flash pieces were cut smaller (to indicate their brevity) and kept getting lost. Still, it was fun and hands-on in ways writing isn’t. And time-consuming.

How long does your revision process typically take? Which piece did you spend the most time revising?

A long time! But it varies so much, too. I never know exactly if it’s going to be an easy revise or a this-is-going-to-take-years situation. I wish I did. I frequently need to rely on other readers’ perceptions of whether a piece of writing is “finished.” Or I require a lot of distance, months and years of distance to see a piece clearly. “The Snow Children” took years–many, many years.

In a previous interview with Laura Madeline Wiseman at The Chapbook Interview, you were asked about “work that is hybrid or genre-confusion.” You said, “The chapbook offers the writer the opportunity for playful, joyful exploration.” Of all the pieces in Please Find Us, “When A Child Dies (Bear It Away)” seems to play with genre the most, combining poetic elements with prose. Can you tell us a little bit about the process of writing it?

I sure can!

I wrote this piece while I was taking an experimental fiction class with Tantra Bensko (through UCLA Extension Writers’ Program where I teach online) and listening to the audiobook version of Flannery O’Connor’s The Violent Bear It Away. My reaction to the novel—or at least an aspect of the novel—was so strong I had to write about it. But I wrote about it in a way that reflected the experimental work I’d been reading. It was originally a two-page piece—more poem than story but kind of also neither—but the brilliant Meg Pokrass suggested it be pared down to that final paragraph.

Though highly entertaining, “Jane” doesn’t immediately seem to fit in this collection. Can you tell us about the inspiration for this story about a ten-pound hamster and why you decided to include it in Please Find Us? (Bonus question: Do you have any pets?)

I have a delightful dog named Winston. He’s from the Pasadena Humane Society and was featured prominently in electronic advertisements between 2015 and ’17 for their Wiggle Waggle Walk fundraiser. This is a great source of pride for me. But I used to have hamsters. Many of us did, right? A couple dear writer friends and I wrote a collaborative piece about hamsters and “Jane” is from a section I wrote. Jane is wonderful and monstrous and deserves to be found.

Both “Little House, 1979” and “The Slide” have a character named Erin. Are they the same person? Are any of the unnamed characters in the chapbook repeated characters as well?

Yes! And in some alternate-reality way, the narrator from “We Used to Play at Kmart” is also Erin. There aren’t any other overlaps in the chapbook that I can think of, but I do have several stories featuring characters from “The Snow Children”. Molly is a first-person narrator in one of them—that’s also the story with the great dog. I really like that story, particularly because it took years to figure out how to write it—to find that entry point—and once I did, it went pretty fast.

The title of the chapbook, Please Find Us, comes from the last sentence of “So You Survived the Apocalypse?!” Why did you choose this phrase for the title of the chapbook? How does the theme of “please find us” relate to the rest of the pieces as a whole?

My favorite part of that flash is the last sentence. It’s hard to come up with a compelling title. Once I realized how much I liked that line, that it seemed title-worthy, I considered what in my body of work spoke to the title. I wasn’t necessarily planning to pair a full-length short story with a bunch of flash, but it made sense when I read the pieces together. I’m almost always writing about characters struggling to understand the world around them, people reaching for connections and thwarting them simultaneously, people who don’t always admit to wanting to be heard, seen, found.

*

Wendy Oleson is author of Please Find Us(winner of the Gertrude Press 2017 Fiction Chapbook Contest) and Our Daughter and Other Stories(winner of the Map Literary 2016 Rachel Wetzsteon Chapbook Award). Her fiction has appeared in Cimarron Review, Crab Orchard Review, Copper Nickel, and elsewhere. She teaches for the Writers’ Program at UCLA Extension and Washington State at Tri-Cities. Wendy lives with her wife and dog in Walla Walla, WA.

*

Find Wendy on Twitter: @weoleson