“I do believe that the best poems are prayers that speak to everyone.”

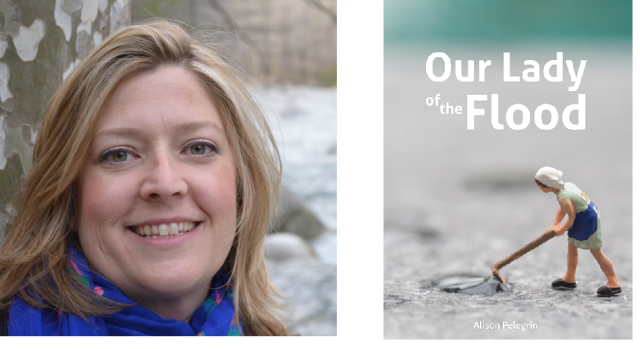

Our Lady of the Flood (Diode Editions, 2018)

There is a prevalent influence of religion in your works. In your chapbook Our Lady of the Flood, numerous poems focus on apparent Catholic ideals and words. When writing poems about such topics of hurricanes and other disasters, do you see the spirituality within the inspirations around you or do you see images and hear stories and apply religion to it afterwards?

Growing up in New Orleans I was exposed to a lot of Catholic culture though I myself am a lifelong Episcopalian. I have been called a cultural Catholic, and I think that is a good term. Traditions from multiple religions permeate the saints and sinner culture of New Orleans, from Mardi Gras celebrations, to All Saints Day, voodoo, and beyond. When I am writing I do not “apply religion” to a poem–that would be decoration. When I am writing, or looking for ideas, I am open to anything. I don’t go hunting down any specific type of poem. As for the poems of mine that seem spiritual, I will say that spirituality is threaded through my life in many ways. It is only natural that if often finds its way into poems, along with a healthy dose of the profane, I might add.

As a writer and a poet who focuses on religious themes, how do you write in authenticity and transparency without coming across as having poetry that is a type of sermon or catechism? As I am writing and my topic turns to religion or spiritual things, I want to come across as unbiased and not as trying to force such ideas into my readers; but, I still want them to think about such things whether they believe in it or not.

I do not spend much time worrying about if I am preacher to the reader or not. I guess I would ask myself, if I felt a poem was “too religious,” if it could mean anything to a reader outside of my faith tradition. If the answer is no, that could be a sign that I am making a mistake–not by preaching, but by writing bad poetry.

In an interview with The Southern Review in 2016, you were asked about another of your fiction pieces, Waterlines and how the poem within it, “Poem Folded into a Boat and Offered to the Bogue Falaya” has religious like qualities and how all poetry is a universal type prayer. How do you approach the idea of universal prayer language within Our Lady of the Flood when their topics seems specific to the Southern region of the US?

I do believe that the best poems are prayers that speak to everyone. The poem that you refer to was a magic poem that came to me all at once and very quickly. My sons and I walked over to a rail-to-trail bridge that crosses the Bogue Falaya and tossed it in after church.

What makes the poem “Our Lady of the Flood” comprehensive enough to make it the title of your chapbook? Does it have any special significance to you in the way that it addresses either the disaster theme or the South itself?

I wrote that poem in 2016 in August and September, after Louisiana experienced some of the worst flooding it has ever seen. The idea for the title came from a photo that I believe I saw on the NOLA.com Instagram page. The photo was of a couple in their post-flood uniform of cut-offs and tee shirts walking outside of an aluminum boat that they pushed through standing water. Inside of the boat was a statue of Mary, and I even think the caption was Our Lady of the Flood. I never saw that photograph again, so I don’t know who to credit, but I would love to thank them for their redemptive act of witness and also to purchase a print.

As I said, I wrote the title poem during one flood in 2016, and I put the book together almost a year later while Texas was enduring Hurricane. It is so troubling to see communities and families undone by water. I always feel the urge to do something, and this time I ended up putting together a chapbook manuscript. I sent it out one time and was lucky that it ended up being a winner of the Diode Chapbook Prize.

Within Our Lady of the Flood are there any pieces that stick out or don’t follow the same theme or style? If so, what is their function for not following the same pattern or theme as the rest of the chapbook?

The poems in Our Lady of the Flood are not stylistically similar, but they are thematically connected either by water or flooding and its aftermath.

In you poem “To the Recruitment Office of the West Tammany Parish KKK” you begin a conversation with this controversial party. How do you effectively engage with controversial topics such as this?

Absolute rage led me to the writing of this poem. I woke up to ignorance and hate–not only in my driveway, but in every driveway up and down the road where I live. I simply wrote about how I reacted on Martin Luther King Day, 2016: I walked up and down the road collecting baggies weighted down with sand and hate-spreading flyers promoting the KKK because I didn’t want my neighbors to wake up to that. I was infuriated. When I got home I wanted to start a fire or something, but then I realized it would be better to mute the hateful messages by folding the papers into origami swans–I have a picture if you would like to see it.

In terms of attaining “Poetry of Witness” within Our Lady of the Flood, what do you hope to achieve by writing about such crises and events like Hurricane Katrina and the flooding in the South? Do you want to merely share survivors’ experiences or perspectives, like in the poem “Anything We Want,” or do you want people to act after reading your poetry?

The poetry of witness is important if for no other reason than to say to another human, “I see you.” When it is my catastrophe I am writing about, I just want someone to listen. To see me. After Katrina, when I was bouncing from hotel to hotel with my family, I felt faceless. We were treated beautifully by the people of Mississippi, but I felt I had no identity outside of “refugee.” I hated being gawked at, and I keep that in mind when other people are experiencing displacement due to hurricane–I see them, but I do not gawk. These are people’s lives, not jokes or memes to pass along.

In your poem “Daydreaming at a Hotel in Mississippi Three Weeks Post-Katrina”, you write this beautiful imagery of wanting to be a bird in the context of the trauma and subsequent aftermath of Katrina. Why did you choose to use birds as your comparison? The dove seems to fit into the religious theme that you so often cover but what are the other strengths of having or wishing for the perspective of a bird?

That poem is weird–it’s actually from the perspective of a younger speaker, and it is part of a novel in verse that I abandoned. The idea for the bird came from something that I saw when I evacuated to Mississippi–there was a little boy at the hotel with a pet bird. I can remember him looking down on us in the swimming pool with that bird on his shoulder.

How do you write about tragedies like Hurricane Katrina without coming across as a sensationalist writer? As an aspiring writer myself, I want to be able to write about my own culture and how it affects me enough that I want it to change but I don’t want to come across as merely using the emotional aspect of the piece to reach for the provocativeness needed for change.

Writing about Katrina isn’t sensationalist because it is my experience. I think that if you “stay in your lane” you should be fine as a writer. To be fair, I feel like I should point out that there are many people who would disagree with me on this issue. I think that tragic events evoke a desire for poetry and often inspire writers–this is a different kind of personal writing, and it is fine, but you have to have the good sense not to publish work that is a quick reaction, especially to something that you are experiencing as a spectator.

What are some tips for young or new writers regarding compiling a chapbook? How much time do you take in deciding which pieces fit within your chapbook and arranging the selection to be a unified collection?

I think that chapbooks work best when they are thematically unified in some way. My advice would be to avoid thinking about a chapbook until you have 30 or 35 pages of poetry that feel connected. Then I would start thinking about how the pieces fit together, and I would be looking for an excuse to drop ten pages so that only the finest work is left. The ordering of each of my books has a separate story. Our Lady of the Flood came together very quickly–over a period of a few days when I was watching the horrific flooding in Houston and remembering the floods of my life.

What are your favorite literary journals to either follow or submit to? Do you follow journals based on their aesthetics or because they have a diverse range of submissions that broaden your literary context?

I love literary journals–there are so many to recommend. The Southern Review and The Cincinnati Review have been very good to me. I also love the American Poetry Review, Tin House, Creative Nonfiction, and the online journals Brevity, Diode, Waxwing, and Blackbird. I submit to or have published with all of these markets. I am drawn to the work that they publish.

What types of literature do you read or what authors do you follow that directly impact your writing or your view of writing?

I read everything that I can get my hands on. Of course I love poetry (Barbara Hamby, Tracy K. Smith, and Catherine Barnett are a few of my favorites) but I also love to read novels and nonfiction, especially shorter pieces, such as those found in Heating and Cooling by Beth Ann Fennelly. I read a lot of great material in literary journals–Tin House and The American Poetry Review are a few favorites, not to mention the interviews in The Paris Review. I also enjoy reading long form journalism.

How do you feel about marketing your writing online through social media like Twitter? Do you find it effective to use these sources or do you prefer to build a reputation through word of mouth or physical outreach?

Though I find Twitter to be high pressure and not an ideal vehicle for my voice, I do consider a social media presence essential to the marketing of poetry. Word about an exciting poem gets around fast, and I think that the poet is obligated to be engaged. While there are poets who manage to sell plenty of books without a presence on any social media platform, I think the norm would be the opposite. A publisher will ask for all of your online platforms when deciding how to market your work. Diode, the publisher of Our Lady of the Flood, does a wonderful job with this.

*

Alison Pelegrin is the author of four poetry collections, most recently Waterlines (LSU Press), as well as Our Lady of the Flood, winner of the Diode Chapbook Prize. The recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Louisiana Division of the Arts, she has poems forthcoming in Tin House and The Bennington Review. She teaches English at Southeastern Louisiana University and lives with her family in Covington, Louisiana.

Find Alison at Twitter at:

@Alisonpelegrin