“I think book or poem titles provide an opportunity to contemplate a word in all its possible dimensions, its richness, and how the same word can hold conflicting emotions in tension. Something that is ‘latched on’ is secure, but it is also something that can’t be escaped.”

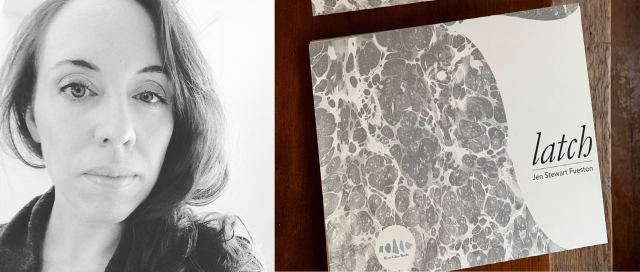

Latch (River Glass Books, 2019)

Valeria Ramirez and Matthew Taylor: Your website mentions that you hold degrees in rhetoric, composition, and literature. How do rhetoric and poetry interplay in your work?

Probably the most significant thing that my rhetoric training has brought to my poetry has been an awareness of writing to and for an audience. I don’t mean in a sense that poetry must always be performing to expectations, but understanding that what is happening on the page can be purposeful and aimed at connecting with a reader. Contemporary poetry can have a reputation for being opaque or impenetrable to readers outside of small academic circles. Rhetoric provides many tools for writers to make an impact on listeners/audiences, and I’ve found I’m much more conscious of using those tools for emotional connection in poetry than I once was.

VR and MT: You note that one of the poems in Latch, “To the Women Marching, from a Mother at Home,” was very timely, that you didn’t know if you had “ever felt the urgency of a poem at that level before.” How did you channel that sense of urgency into your work, and where else does it appear in Latch?

“To the Women…” is an occasional poem — one written intentionally to mark an occasion or date in time. It was an unusual activity for me to write that kind of poem, and even more unusual to share it as widely on social media as I immediately did (that kind of “unpublished” sharing of work being perceived as being slightly unprofessional). I have found myself writing more of these kinds of politically and socially charged poems in recent years, however, mainly because it feels like it would be shameful and oblivious to be living at this moment in time and not meaningfully engaging with it. My recently published poem, “Revised Common Liturgy,” was a direct response to the National Day of Prayer in 2018, and other poems in Latch, like “Common Loon” (a response to a news story about declining bird populations) and “Pablo C. Tiersten, 38, Kansas City” (an elegy for a man who took his life during an altercation with police), are tied directly to actual events.

I think poets have a unique and much-needed ability to speak about current events in language that goes beyond the factual, but which engages imaginatively and empathetically with those around us. Writing “Pablo C. Tiersten,” enabled me to enter, briefly, into imagining another person’s final moments and what grief and terror must have driven him to, an experience I found incredibly moving. Writing that poem became a sacred act of honoring someone I might never otherwise cross paths with. It can be overwhelming to try to process all the distressing news of each day, and the temptation to simply let it wash over me without feeling or grieving it is great. Writing these kinds of poems is a way in which I let my heart participate in the world’s sorrows, and that keeps me awake to life rather than numb to it.

VR and MT: “Desert Parable,” another poem in Latch, seems to lack an obvious connection to the chapbook’s central theme of motherhood. Could you talk about why you decided to include this poem?

I included “Desert Parable” because the early childhood years are, for many if not most mothers, a time of scarcity — scarcity of physical and mental energy, personal time, personal space, adequate rest, etc. etc. etc. The first months and years with a baby, it can feel (it felt for me) like a very solitary and precarious time when I was making due with very little relational or physical input. It was a desert, but one in which I had to “do much with little” as the poem says. There’s a child to feed and grow. There’s creative work asking to be given attention. There’s the tiniest glimmer of life in a given day which needs to be nurtured and attended to. The desert plants that grow slowly, in dry spaces, storing up whatever little water they get in order to survive until the next rain — they were a good parable for me at that time of my life with very young children.

VR and MT: The poems in Latch, from what I can tell, are selected from your output during the last few years. Do you write poems with a finished collection in mind, or do you piece together poems you’ve written in the past when assembling a collection?

Latch was different than my first chapbook, Visitations, because I did write the individual poems with a finished collection in mind. I intentionally wrote many of the Latch poems while I was still nursing my second son because I wanted to live deeply into that bodily experience and simultaneously connect it to creative work. There are poems in Latch that I wrote while lying on the floor of my son’s nursery in the middle of a night feed, and there are also some that were written before he was conceived while I was on medication for infertility. I suspect going forward in my writing, I will usually write with a collection or theme in mind, though there is always the individual poem that pops up and asks to be written. Knowing how to navigate between those two impulses is something I’m still learning how to do.

VR and MT: Your poem “Taking the Baby to See Rothko at the National Gallery” seems to be extremely specific. Did you actually take your baby to the national gallery? What sparked the idea for writing a poem about it?

“Taking the Baby to See Rothko” is a good example of a poem I wrote intentionally with the broader project of Latch in mind. During the time I was generating poems for the book, I took my 9-month-old on a short trip to Washington DC during the annual AWP conference, toting him around in Ubers with his car seat and strolling him through the giant book fair on the open-to-the-public Saturday. The rest of our time there, I took him to a few of the Smithsonian museums, but we liked the National Gallery best. The Rothko poem came out of that time with him there, as did the ekphrastic poem “Interior of Oude Kerk, Amsterdam,” which caught my attention because of the prominence of a nursing mother in the painting. Looking at art with a baby in tow caused me to filter my viewing through his reactions, and also to look at the images for women who reflected myself back to me — women who were doing the essential but unglamorous work of feeding, clothing and caring for children.

VR and MT: In many of the poems in Latch, you allude to Mother Mary in expected situations such as a church, but also in unexpected places, such as the mall. Why is Mary such a big theme in your chapbook and what do you hope readers take away when they run into her in the more unexpected places?

Though I am not Catholic, growing up in the Evangelical church the figure of Mary provided a model — often the only female model — of how to be a vessel available for God’s purposes. For many years and through many poems, I’ve held as a touchstone the moment that Mary responds to the angel saying, “Let it be to me as you have said.” It’s an essential moment in the life of a disciple, a woman, and an artist. Mary’s yes is a moment of opening, of allowing her very body to become a co-creator with God and a conduit for the coming of grace into the world. Mary shows up in my poems and in unusual places because I think it’s worth considering how her example of receptivity to the Holy Spirit might play out in lives all around us, every day. My hope is that her presence in the book helps illustrate the complexities of the messages we receive about what it means to say yes to God, or to something larger than ourselves that demands our attention and energy, whether it’s bearing a child or participating in a political protest.

VR and MT: In the beginning of your chapbook, you include a page with all the different definitions of the word “latch.” How did you come up with the idea to do this, and which definition do you believe represents the chapbook as a whole the most?

The most obvious meaning of the word Latch for this book is the meaning used in breastfeeding when the infant has successfully latched on to the mother. That very intimate and vital connection was a fruitful image to contemplate as a central metaphor for the book. There are a lot of other resonances, however, when you think about a latch as something that opens or closes or fastens. Having a child closes certain doors, and opens new ones. I also really liked the specific linguistic use of the term “latching” as a communicative act in which one speaker begins an utterance and another speaker continues it. That struck me as a lovely parenting metaphor as well. I think book or poem titles provide an opportunity to contemplate a word in all its possible dimensions, its richness, and how the same word can hold conflicting emotions in tension. Something that is “latched on” is secure, but it is also something that can’t be escaped.

VR and MT: What other subject matters or themes do you wish to tackle in your future poems?

I’ve noticed that many of my poems over the past year have been wrestling with some of the short-sighted or misguided theologies I grew up with inside 20th century American Evangelicalism. I have been unpacking the repercussions of some of these teachings (e.g. so-called “purity culture,” Christian attitudes toward environmental issues, etc.) both for my own life and for broader society. I believe that theology manifests in behavior, so sometimes we can trace negative or harmful outcomes to flawed theologies. Likewise, beautiful and right beliefs flower into beautiful realities. This sounds a little esoteric, but hopefully my poems can pin down more concretely the ways our ideas about God, nature, and human relationships bear fruit for good or for ill.

Jen Stewart Fueston lives in Longmont, Colorado. Her poems have recently appeared in The Christian Century, Mom Egg Review, and Harpur Palate. Her first chapbook, Visitations, was published in 2015, and her second chapbook Latch was just released by River Glass Books. She has taught writing at the University of Colorado, Boulder, as well as internationally in Hungary, Turkey, and Lithuania.

Find more at jenstewartfueston.com