“My best advice is to write characters who intrigue you; that way, if you can’t figure them out at first, you’ll be willing to keep trying.”

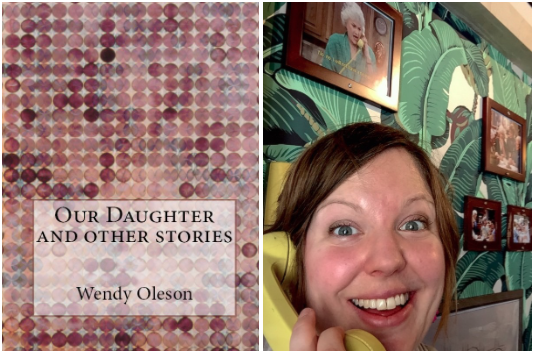

Our Daughter and Other Stories (Map Literary Rachel Wetzsteon Chapbook Award Series, 2017)

Could you explain how you were introduced to writing?

Growing up, my school district (West Des Moines, Iowa) followed the Whole Language approach to language arts instruction, and we had time to free write what seemed like every day. My memories of writing begin in first grade. A couple “stories” I wrote: “The Bubblegum Watch,” and “All of the Songs from the Sound of Music Except One.” In truth, I was missing more than one song, but I knew enough not to attempt to transcribe the yodeling-goat-herd number by memory.

How were you introduced specifically to flash fiction, and how has the genre shaped your writing career?

My former professor, Judith Slater, introduced our fiction workshop to Susan Jackson Rodgers’s short shorts in the spring of 2010. “How I Liked the Avocados” was my first attempt at flash. It required less revision than nearly anything I’d written, which was rather ideal.

What genre has had the greatest impact on you as a reader?

All of it? I guess I’m torn between novels and short stories. I first fell in love with reading through books like Charlotte’s Web, Bunnicula, and Watership Down, and losing myself in a novel is a great feeling. That said, I’ve spent the last several years reading more stories and story collections than novels, and I’ve come to appreciate the many indie presses (A Strange Object, Dzanc Books, Split Lip) publishing beautiful and innovative collections.

Do you have a favorite genre to write? If so, is it hard to put aside your affinity for that genre in order to write something in another genre?

Fiction and hybrid texts—I have fewer hang-ups about those than I do with pure poetry or creative nonfiction. At the same time, I relish starting a piece without knowing how long or what genre it will be; I like letting the work decide for itself.

When you are writing, do you have a vision for a collection or a longer work, or do you eventually sort through individual pieces that you find have a common theme?

The majority of the time it’s the latter; occasionally, however, I’ll be working on a specific project—linked stories, for example—or I’ll have what feels like a hole in a collection that needs addressing.

What are a few of your favorite pieces of literature?

Some recently-published short story (or flash fiction) collections I’ve loved:

Dead Girls and Other Stories (Emily Geminder)

The Subway Stops at Bryant Park (N. West Moss)

Felt in the Jaw (Kristen N. Arnett)

The Dog Looks Happy Upside Down (Meg Pokrass)

Man & Wife (Katie Chase)

Bystanders (Tara Laskowski)

Her Body and Other Parties (Carmen Maria Machado)

Difficult Women (Roxane Gay)

The Visiting Privilege (Joy Williams)

In your interview with Tara Laskowski, you said, concerning your story “How I Liked the Avocados,” that you didn’t know if there actually was a fourth avocado or where it would be if there was one. How much do you know about the characters you create? Are they sometimes as mysterious to you as they are the reader?

I know nothing about these people! Really, they are mysterious, and that’s what keeps me interested.

Our Daughter and Other Stories repeatedly brings up the theme of mother and daughter. Can you comment on what drew you to this theme?

I didn’t wholly realize this until N. West Moss mentioned it in her generous blurb. I was thinking more about the children in the manuscript, less about those corresponding mothers even though they are very much present (or present through absence). Children fascinate me, and grown-up children with their own children—they fascinate me too.

I was very impressed with “Story of a Room.” In the story, you seem to blur the line between poetry and prose, breaking the story into stanza-like fragments and even using enjambed lines. Did you originally intend to write this piece in that way or was this a poem that you felt would work better as a short story?

I wrote “Story of a Room” for Tantra Bensko’s Experimental Fiction course (UCLA Extension Writers’ Program), which I took with the hope that experimentation and play would help me find joy in creative writing again. I realize now that I’ve never properly thanked Tantra for helping me get to that place. Her weekly lectures and assigned readings were great, and I felt so encouraged to just do whatever I wanted—no expectations. I remember this sort of image of a golden room came to me along with the phrase “yellow loaf,” and I literally just went from there; the whole thing unspooled almost magically.

“We Used to Play at KMART” was a chilling story. You manage to grip the reader in just one page. Could you offer any strategies you’ve learned in quickly getting the reader engaged and how to, once you have their attention, cause such a sudden turn?

I really struggled with this piece; it took years to get right. I’ll often try to engage the reader through sensory description and voice-driven prose, but this doesn’t guarantee a story; it took several drafts before I understood why the narrator was speaking and to whom. My best advice is to write characters who intrigue you; that way, if you can’t figure them out at first, you’ll be willing to keep trying.

My favorite piece in the collection was “Pin: A Fairy Tale.” Other pieces in the book seem very grounded in reality, but this piece gets into the realm of magical realism. Can you discuss your inspiration for this story and your choice to make it one that stretches the reader’s imagination?

I wish I could remember! I wrote it in 2011 while taking a class with Kate Bernheimer; the best I can say is that Kate and my classmates inspired me! Matchbook Lit originally published “Pin,” so you can find my accompanying “Critical Thought” here.

Why did you choose the title story “Our Daughter” over all of the others to represent the collection as a whole?

When I’m sending out work, I’ll often discard decent titles in favor of something impulsive. Or I’ll pick something overly-safe. But this title felt right. I chose Our Daughter and Other Stories, however, because I liked that it referred not only to the flash piece within, “Our Daughter,” but also the idea that we tell ourselves stories of who our daughters are.

Could you comment on the character of Kella from “The Glass Girl”? I found her character remarkably relatable and foreign at the same time. She loves space and imagining like other children do, yet statements like “You will polish me down to nothing” and “The faster you rub, the better I read your thoughts” make her distant and somewhat cold. How did you think of this character, and what was it like thinking through her development?

Kella is a fairy-tale protagonist, a little flat and very unafraid. I suppose I’m much more like her mother. If Kella were warmer and more empathetic, she might be consumed by her mother’s grief. Kella has serious boundaries, and that’s not such a bad thing.

*

Wendy Oleson’s stories, poems, hybrid, and collaborative texts appear in Passages North, [PANK], Crab Orchard Review, The Normal School, The Journal, and elsewhere. She’s received fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center and serves as editorial staff for Fairy Tale Review and Memorious Magazine. Wendy teaches for the Writers’ Program at UCLA Extension and Washington State University at Tri-Cities. She lives with her wife and a hiccup-prone dog named Winston in Walla Walla, Washington.

*