“Observe nature, art and people deeply; see details.”

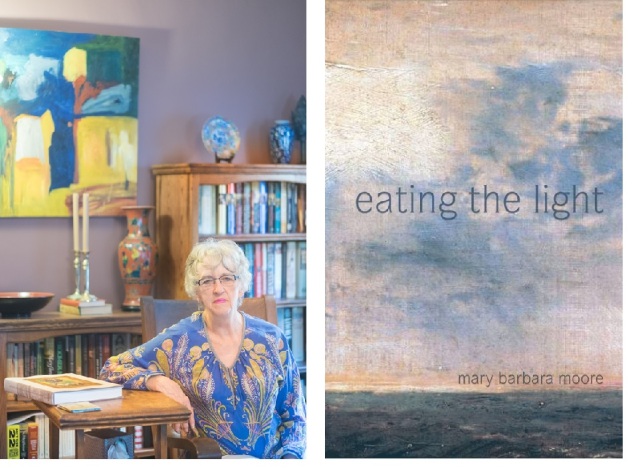

Eating the Light (Sable Books, 2016)

Eating the Light (Sable Books, 2016)

Could you share with us a representative or pivotal poem from your chapbook? Perhaps a poem that introduces the work of the chapbook, or one that invites the reader into the world of the chapbook?

It’s hard to choose just one poem, especially because poems explore three central and several related focuses of seeing, which is a central topic of this book: nature, art, and the female body. Thus, the opening poem suggests the way sight eats both nature and art, devours the world:

Colonizing Eyes

The world shows its hand all at once, a spill

of tangerines, mangos, nectarines,

to the table’s wheat- and earth-hued grain,

which ripples the receiving. Even

the straw-gold cornucopia’s a sign

of plenitude. We are meant to think:

fruit trees breed for my delight.

Looking I swallow orbs of orange

and peach-blush red, puckered

stem-holes, oblation of rounded line

to rounder things. Eating I fill out.

The caught light anoints my arms

in swaths: I’m oiled and muscled,

cut like circus strong men.

There’s no need for stealth, only strength

and health: The world is ripe for my taking.

Even the birds think ripe thoughts,

round-bodied, embowered like fruit.

Magnified, the paint stroke V’d

symmetrically make feathers

like miniature pines. Each small bird

is nearly a landscape! Such orderly

coats of gloss and reverie.

Why did you choose this poem?

I like its sensory description and the way that it makes the picture a meal, a thing to be eaten by eye. Also, more intellectually, I think it conveys the way Euro-American culture views nature, and in a larger sense, the whole world—as an object “we” are entitled to see and devour. Essentially, viewing the world and other people as objects of use makes all sight “colonizing.” At the same time, as the title puns, eyes that see this way are also colonized, turned into colonizers, not participants in the world. I also think this poem shows my aesthetic in the book, an attention to the details of the poem’s object, its sensory existence. It’s sensuous but also knowing.

Does the chapbook form have an impact on the politics of the poems that appear inside it?

Interesting question! Putting these poems together several years ago revealed a political aspect to them that was less apparent before. The individual poems portrayed or reacted to seeing or being seen in a way that reflected my sense of colonialism’s impacts and the parallels between it and the objectification of women—that is, the way some men (and women) reduce women to mere objects of sight rather than seeing them as fully-fledged humans. We’ve just seen and heard this manifested in the 2016 election.

What obsessions led you to write your chapbook? How did you write the poems?

The chapbook wasn’t written as a book, but collects poems written over a course of years that I gradually saw as related in ways described above. Nevertheless, for years I’ve found poems and metaphors popping up about seeing as eating. Since sight is the central sense for Western Culture, all the way back to Plato et al, it’s no surprise that many of our poems explore vision, but the connection between seeing and eating was the surprising and exciting thing. Over and over, that language, that imagistic connection, occurred. Note that I use the verb, “occur.” It reflects my way of composing: lines, phrases, words “occur.” Then I expand, play, enrich, mess with them. Sometimes I seek out those seed phrases or words, make lists and notes. Only after writing do I see a “theme,” or meaning. Furthermore, schooled in feminism and other literary theory, I don’t believe meaning is singular, but multiple. Only after the poem exists do I see what it might be saying. Poetry is a way of discovery for me, not an after-the-fact recording of insight. Poetry is the insight.

What’s the oldest piece in your chapbook? Or can you name one poem that catalyzed or inspired the rest of the chapbook? What do you remember about writing it?

The oldest poem is 10 years old; the newest was just months old when I compiled the version that Sable published. Many of these questions assume that the chapbook was “written” all at once. Instead it was collected. The intensity and density of some of the poems reflect years of revision and attention to each word, line break, and turn of phrase in many cases. That doesn’t mean I think the poems are perfect! It’s just that all my writing involves much revision, even when, on those wonderful rare occasions, a poem emerges almost “right” in one sitting.

How did you decide on the arrangement and title of your chapbook?

The arrangement emerged more or less as is as soon as I saw the connections between all these existing poems. Perhaps one catalyst was the publication of both the poem “Eating the Light,” and the poem “Colonizing Eyes.” Then I wrote the Turner poem later, quite recently, and I added it. I think it helped clarify the whole project, at least for me. Once I knew that I had a batch of poems about seeing as eating or devouring, I saw that some older poems about the female body that I loved but could never quite see related to other poems were ways of evading that devouring sight. Their depictions of slippages out of physical boundaries and outlines were refusals to be bounded, impinged on by sight. It made sense to divide between natural and human objects of sight then. Opening with “Colonizing Eyes” helped set up that view of vision as eating without bopping the reader over the head with it.

Which poem in your chapbook has the most meaningful back story to you? What’s the back story?

Interesting, again. “Turner’s Sun” emerged after I had visited Italy and seen the Roman aqueduct that he had painted for “The Bridge of Towers.” In a kind of Jungian synchronism, an artist friend had actually sent me a postcard of “The Bridge of Towers” months before I went to the Umbria region of Italy, before I even knew Spoleto was his painting’s site! After the visit to Italy, I did Tupelo Press’s 30/30 project, and as the first prompt, a friend whom I met in Italy sent me a quotation from Richard Cohen’s book, Chasing the Sun, as a prompt for my first day in 30/30. I bought that book, and it turned out Cohen had written about Turner’s suns. In the book, I saw a (poor) reproduction of “The Fighting Temeraire,” which I then looked up on the web. These meaningful coincidences energized the Turner poem about the Temeraire, which I then added to Eating the Light, which had already been circulating.

Which poem is the “misfit” in your collection and why?

“Sea View Lodge” was new and took many revisions to reach its current state, and may still take more revision before I’m fully satisfied. It’s a long and pretty complex poem, and though the grandmother’s are fictional, they import a sense of history and perhaps even colonization that I’m nor sure is actualized yet. Or maybe it is. Who knows?

What was the final poem you wrote or significantly revised for the chapbook, and how did that affect your sense that the chapbook was complete?

See my comments above about “Sea View Lodge.”

Did you read straight through your chapbook out loud during the revision process or while finalizing revisions? If so, how was your experience of the poems different? How were your ideas about their individual meanings changed?

I always read individual poems aloud as part of composition and read the chapbook out loud several times. Reading like that helps me hear awkwardness in phrasing, helps me hear and revise the music.

Describe your writing practice or process for your chapbook. Do you have a favorite prompt or revision strategy? What is it?

My composition and revision strategies are described somewhat above. In general, I write every day, seeking words, phrases, or images in words that energize me in some way, and then building off of those. I write off of my own weird word coinages, or I do automatic writing to get interesting or surprising word combinations. Sometimes I just deeply describe a thing or scene, and then build off that. Many such words or phrases or descriptions go nowhere. When they go somewhere, I allow the poem to form before I worry about its meaning. The sounds of words inspire more words, and I’ve come to think that I have an inner music that I’m manifesting in language. BUT once I have words, I begin to see images. In contrast, some poems begin with what I see. “Eating the Light” actually emerged from detailed and silent observation of maple leaves out of my second-story apartment window. YET in the end, I seek to make meanings through the poems, to discover something for myself but also to speak to someone, so, though poems may begin often in pure play and in sound, or in description, I don’t send them out unless and until they develop meanings. Right now, I do have a persona who can inspire poems, just saying her name, starting a sentence with her name, can lead somewhere…but not always!

What has the editorial and production experience with the press who picked up your chapbook been like? To what degree did you collaborate on the cover image and design of your chapbook?

Sable Books was GREAT to work with. Their graphic artist actually read the book and then suggested covers, sending me four complete designs to choose from. I love the cover. Melissa Hassard, the publisher, supports and uplifts you besides getting the book into physical form.

What are some of your favorite chapbooks? Or what are some chapbooks that have influenced your writing? What might these favorite or influential chapbooks suggest about you and your writing?

I very much like three very recent ones: David Rigsbee’s The Pilot House, Kim Garcia’s Tales Of the Sisters, and Zeina Hashem’s 3Arabi Song. These are small marvels, full of music and image, the poems coming to their sense of meaning through these elements. They reflect a taste for poems that communicate, first of all, rather than mirror the chaos or meaninglessness of contemporary life through a jumble of disjunctive images and phrases. Though the latter styles create some lovely music at times, it seems to me that a mirror held up to meaningless, is well…..

If you have written more than one chapbook or novella, could you describe each of them in chronological order?

Apostle/Thistle explores the spiritual life of a lapsed Catholic; it’s hard to place poems like these which are irreverent yet obsessed with reverence, and it has been in circulation for just over a year.

Amanda and the Man Soul explores the character and life of the outrageously vain, sometimes brilliant Amanda, who also is, by the way, a woman who plays to being seen. Several of the poems have been picked up by Poem/Memoir/Story. It’s brand new as a chapbook and probably will go through more iterations before someone takes it.

What are you working on now?

Imbalance My Dance is a full-length collection of sonnets which rhyme but have irregular line-lengths, so formally they (perhaps irritatingly) combine elements of formal and free-verse. They are funny, dark, contemporaneous in image and diction. It was a semi-finalist last year for the Vassar Miller prize and is in circulation.

Brand-Spanking-New Ms. , title tba, collects poems written mostly in the past year. Its tones and forms are varied, which I like very much––that is variation, as opposed to monotonality. They link through obsessive images about color, the sun, the landscapes of West Virginia and Italy, and it includes odes to family, other poets, and to Turner. Though it has some humorous poems about the persona, Amanda, (described below), which link through imagery of color and through motifs such as doubleness to the other poems, it also has elegaic poems about family. Some from Eating the Light will also appear here.

What kind of world do you think your chapbook creates? What, or who, inhabits that world?

Eating the Light creates a lush, sensory world of landscapes and ocean, of art work, and of female figures who merge into or distinguish themselves from their backgrounds. It’s a painterly world, I think. The women in the book inhabit it, yet always try to evade being contained. Ironically, the poems contain their evasion of containment. The reader I think, if the book works, enjoys the sensory imagery and enters the poet’s eye in order to see in a different way and to recognize what his or her way of seeing might do in the world. Seeing is an act.

What advice would you offer to students interested in creative writing?

We learn how to speak by imitating the sounds and speech of our family. Read great poetry of the past, especially of the 20th Century. Write a LOT. Find one or two older poets who are accepted as “great” by our culture (Rilke, Marianne Moore, Derek Walcot, Elizabeth Bishop, Gwendolyn Brooks, Neruda—TRUE greats) whose work you utterly love, and study how they create image and sound. See how they use physical bodies and embodied things, not abstract ideas, to communicate meaning. (My idea of beauty differs from yours, but if you give me detailed visual images of what you think is beautiful, I “get” that beauty without your even using the word “beauty”). Imitate “your” great poets, initially, and use those imitations to take off in your own direction. (Never try to publish imitations of other poets!) Observe nature, art and people deeply; see details; draw things with details, even if you’re not a good artist: do this to make you see the details, that in a poem, help create meaning. Don’t try to publish until your poems seem as good to you as some of the published poems you love. Don’t use rhymes until you’ve grasped image.

What question would you like to ask future writers featured at Speaking of Marvels?

I love to hear about people’s writing processes.

*

Mary B. Moore’s poetry books include Eating the Light selected for Sable Books by Allison Joseph, and two full-length collections, The Book of Snow, published by the Cleveland State UP, and Flicker, winner of the 2016 Dogfish Head Poetry Award judged by Carol Frost, Baron Wormser, and Jan Beatty. Her poetry has appeared lately in Coal Hill Review, Birmingham Poetry Review, Drunken Boat, Cider Press Review, Nimrod, and earlier in Poetry, New Letters, Prairie Schooner. Work is forthcoming in Georgia Review and Poetry/Memoir/Story. A retired professor, she lives in West Virginia with the philosopher John Vielkind and the cat Seamus Heaney.

*

Pingback: Mary B. Moore | Speaking of Marvels