“My grandfather emigrated from Ukraine to western Canada. I would not have the life I have had he not done that.”

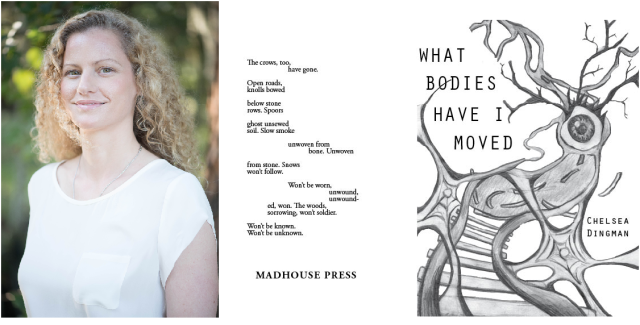

What Bodies Have I Moved (Madhouse Press, 2018)

Could you tell us a bit about your growing up and your path to becoming a writer?

I grew up in a small town in British Columbia. My father died in a car accident in a blizzard when I was nine. I had a wonderful teacher that year who encouraged me to write. I wrote her a book of poems about snow and that ignited my love of writing and poetry.

How do you decorate your writing space?

I write in my home office, which is filled with books and very little natural light, though I have an affinity for lamps. When I’m writing, the space just needs to feel warm and private. I don’t even notice the rest.

What is the relationship between your ethics and your aesthetics? How does your form, content, and style as a writer reflect how you are and are trying to be as a person?

I want the form of my poems to reflect the content of the poems. I don’t necessarily think that either aspect of craft relates to my ethics, other than my desire to write a well-crafted poem. Instead, I think my choices reflect what the poem needs. I try to put myself aside when writing & write in service of the poems.

Could you share with us a poem from your chapbook? Perhaps one that introduces the work of the chapbook, or that invites the reader into the world of the chapbook?

One of the poems from the chapbook, “Reconstructing the Saints,” was recently published on poets.org. The poem is set in 1924 Poland, in a church that is now part of Ukraine. The speaker is migrating west to try to find sanctuary and stability because Ukrainians were not allowed to hold jobs or land after Poland took over that territory. Before WWI, the same territory belonged to Austria-Hungary, so it changed hands many times over the course of a few years.

Why did you choose this poem?

This poem is at the crux of the spiritual and existential crisis that the speaker is confronting: forced out of one’s homeland by church and state following several wars, where would a person turn? Where was anyone safe? What guarantees of safety are offered to anyone, if one cannot have faith in a higher power?

What are some of your favorite chapbooks? Or what are some chapbooks that have influenced you?

Some favourites from the past year are: Little Climates by L.A. Johnson, teaching my mother to give birth by Warsan Shire, & Equilibrium by Tiana Clark.

What might these chapbooks suggest about your writing?

They suggest that I like to read women and that my work tends to respond to women’s issues, such as personal exile, whether in this century or the last.

What obsessions led you to write your chapbook?

My grandfather emigrated from Ukraine to western Canada. I would not have the life I have had he not done that. His life was hard. I really wanted to write something that honoured that struggle. As an emigrant myself, my obsession with this loss of home, or possibly the idea of home, resonates in my work. My obsession was to write the rootlessness of immigration: my grandfather felt displaced and disowned his whole life. He never belonged anywhere again, maybe not even in his own skin. I find that so tragic and unnecessary.

What’s your chapbook about?

My chapbook is about the speaker’s emigration from Poland to Canada in the second wave of immigration in 1924. It concerns the way we are moved through landscapes also: walking on land, by train, by boat. How each mode of transport changes that experience.

What’s the oldest piece in your chapbook? Or can you name one poem that catalyzed or inspired the rest of the chapbook? What do you remember about writing it?

All of the poems were written in the fall of 2016. I was taking a grad class with the poet Jay Hopler. The chapbook, which is part of my thesis, resulted from an assignment to write an imaginary walk from somewhere in the world that I’d never been. I had to research 30-50 miles per week. It quickly turned into a full manuscript.

How did you decide on the arrangement and title of your chapbook?

I had help with the title from my most trusted reader, the poet John A. Nieves. My full manuscript has a different title. This new title is two lines from a poem inside the book. I arranged the poems based on how the speaker would have moved through the world at that time, based on my research.

Which poem is the “misfit” in your collection and why?

The poem, “To the Last Traveler,” featured on the back cover, is the biggest departure from my personal style. The argument of the poem is largely derived from sound & language. I am usually a more narrative poet.

What has the editorial and production experience with your press been like? To what degree did you collaborate on the cover image and design of your chapbook?

Madhouse Press has been so wonderful. I collaborated on everything. I sent the editors ideas for the cover based on gorgeous surrealist art by Ukrainian artists. They had an independent artist design the cover with that in mind. I approved the fonts, the font sizes, the art: they are phenomenal to work with. Because they are poets, I really trust their vision and their suggestions. Because they are a small press, I love the collaborative process that I was able to engage in. It’s really been such a great experience (poets: do send them your work!).

If you have written more than one chapbook or book, could you describe each of them in chronological order?

My first book, Thaw, was chosen by Allison Joseph to win the National Poetry Series and published by the University of Georgia Press in 2017.

What are you working on now?

I recently finished my third manuscript about infertility and stillbirth. Now, I am researching a collection of poems about traumatic brain injury and its affects on professional athletes.

How do you contend with saturation? The day’s news, the flagged articles, the flagged books, the poetry tweets, the data the data the data. What’s your strategy to navigate your way home?

I read poetry. I write poetry. I read poetry. I kiss my kids. I marvel at my students. I marvel at other poets’ work. I read poetry.

What advice would you offer to students interested in creative writing?

Read everything. Write a lot. Forget about trying to write something great and just write. At some point, the writing will get better. Keep writing.

*

Chelsea Dingman is a Canadian citizen and Visiting Instructor at the University of South Florida. Her first book, Thaw, was chosen by Allison Joseph to win the National Poetry Series (University of Georgia Press, 2017). Her chapbook, What Bodies Have I Moved, is forthcoming from Madhouse Press (2018). In 2016-17, she also won The Southeast Review’s Gearhart Poetry Prize, The Sycamore Review’s Wabash Prize, Water-stone Review’s Jane Kenyon Poetry Prize, and The South Atlantic Modern Language Association’s Creative Writing Award for Poetry. Her work can be found in Ninth Letter, The Colorado Review, Mid-American Review, Cincinnati Review, and Gulf Coast, among others. Visit her website: chelseadingman.com.