“I wanted to write into [the] opening created by bewilderment.”

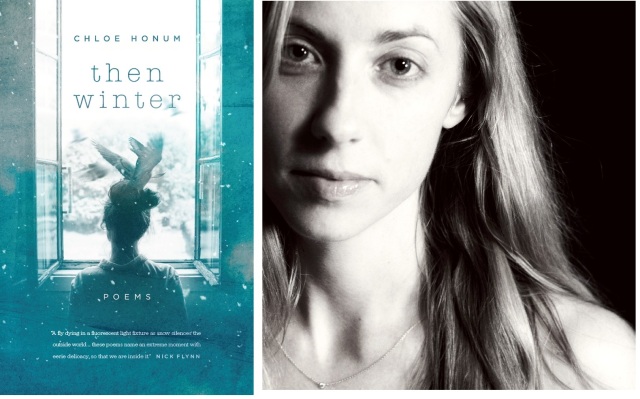

Then Winter (Bull City Press, 2017)

What is the chapbook about?

In terms of narrative, it’s about the speaker’s experiences as a day-patient in a psychiatric treatment facility. It’s also about longing, the seasons, survival, and beauty.

Could you share with us a representative or pivotal poem from your chapbook? Perhaps something that introduces the work of the chapbook, or that invites the reader into the world of the chapbook?

Late Afternoon in the Psychiatric Ward

The fluorescent light

goes off and the shadows

fall apart like a cardboard fort.

The invisible should be sturdier,

like that stormy summer

the rain came so heavy

the waterfall was just

a thicker column of sky.

Now a fly throws itself

down on the formica table

and buzzes and spins

on its back, quickening

the poison. It resembles

a word scribbled out.

Won’t do, won’t do.

But oh you of the river-

wet lips, I miss you

this moment, and this.

Why did you choose this poem?

This poem brings together several of the collection’s themes. I’m interested in what happens when desire is brought into what could be perceived as an unlikely setting. Of course, there’s really no unlikely setting for desire, but I think there’s a particular spark that occurs when harsh or unpleasant moments (the fluorescent light, the dying fly) come up against passionate moments.

I’d also been thinking about Fanny Howe’s description of bewilderment as an enchantment that “breaks open the lock of dualism (it’s this or that) and peers out into space (not this, not that).” I wanted to write into that opening created by bewilderment. It’s strange, but sometimes that gaze can actually lead to clarity, or to the distilled image or thought. When I open myself to the wonder of “not this, not that”— or “Won’t do, won’t do,” in the case of the poem above— I think I actually get closer to being able to fully enter the clear moment (“I miss you”).

What obsessions led you to write your chapbook?

I was thinking a lot about silence, and I was feeling its weight. I lost my mother to suicide when I was 17. She was 47. Both in my life with her and after her death, I learned a lot about the harm of stigma and the deadly climate of silence surrounding mental illness and treatment. I’m grateful that in writing these poems I was able to feel my way through that silence and to press against it. That pressing—a way of opening a space previously enclosed in silence—is why I love poetry. I also wanted to honor the setting of the psychiatric ward in the book as a deeply human place, full of beauty, terror, pain, struggle, tenderness, grace, and humor.

How did you decide on the title of your chapbook?

The title comes from a moment in the poem “Group Therapy”:

“Beyond the window, autumn toys with ideas of heaven. The trees become fiercely talented and focused. Then winter.”

I liked its feeling of sudden change and inevitability—no choice but to take that deep shift. Throughout the book there’s a lot of nature and a lot of shifts in the seasons.

Which poem in your chapbook has the most meaningful back story to you? What’s the back story?

I wrote the poem “Offerings” shortly after the 17th anniversary of my mother’s death. She died when I was 17, so on that anniversary I had lived 17 years with her, 17 years without. It was an astonishing thing to realize, and I was unprepared. I hadn’t thought about the significance of the anniversary until I was standing right in it. My life felt folded in half, with her death at the seam.

I wrote the first draft of the poem in the middle of the night, after waking with the opening line in my head. I was living at the time in Bend, Oregon, in a little apartment with a balcony that overlooked the Deschutes River. It was so beautiful there, and the beauty was intensified by my missing her.

(read “Offerings” below)

What was the final poem you wrote or significantly revised for the chapbook, and how did that affect your sense that the chapbook was complete?

One of the last poems I wrote for the chapbook is also the last poem in the collection: “Teaching Poetry at the Juvenile Detention Center in Fayetteville, Arkansas.” That detention center is a horrible place. I was surprised that the poem ended with hope. That’s part of how I knew the chapbook was near complete: I had come to a moment of urgent and explicit hope.

(Read “Teaching Poetry at the Juvenile Detention Center in Fayetteville, Arkansas” below.)

What has the editorial and production experience with the press who picked up your chapbook been like?

My experience with Bull City Press and Ross White, the brilliant executive director, has been wonderful. I’m really honored to be on a press with some of my favorite poets writing today, like Jill Osier, Tommye Blount, Emilia Phillips, Anna Ross, Tiana Clark, and Anders Carlson-Wee. I’m so grateful that the collection found such a caring, inspiring, hard-working home.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on my second full-length collection, tentatively titled Birthday at a Motel 6.

What advice would you offer to students interested in poetry?

Come to poetry with the understanding that it will change you. It will help you grow. Part of the real work is to let it.

*

Chloe Honum‘s first book, The Tulip-Flame (2014), was selected by Tracy K. Smith for the Cleveland State University Poetry Center First Book Prize, won the Foreword Poetry Book of the Year Award and a Texas Institute of Letters Award, and was named a finalist for the PEN Center USA Literary Award. She is also the author of a chapbook, Then Winter (Bull City Press, 2017). She has received a Ruth Lilly Fellowship and a Pushcart Prize. She was raised in Auckland, New Zealand.

*

Offerings

I have saved my pantomime of the sky for you. Let me lie with my head in your lap. I will sing the song of the trees in the cold wind, the way they rush up like flames, their leaves rippling. I want to show you everything you might have missed. With my fingers I will emulate moonlight resting on a field of violets. I am about as convincing as the child playing the sun in the school recital. But I have rain in my hair. This much is true. Let me bring it to you.

*

Teaching Poetry at the Juvenile Detention Center in Fayetteville, Arkansas

It’s cold and the light is blurry,

the fluorescents spasming,

the walls a steely gray.

Each child is given a pencil.

Their cells are just beyond

the heavy sliding doors.

They write get-away poems

and tree-house poems.

Sack of weed and siren poems.

A flea appears on my arm and

quivers, like a fleck of onyx.

I watch it bite and gleam and the boys

sitting across from me

watch it, too. In a cement

tomb, hope is anything

that travels in big leaps.