“I think it’s those weird and specific details that make abstract ideas like colonialism or gender politics or environmental impact into something human and moving.”

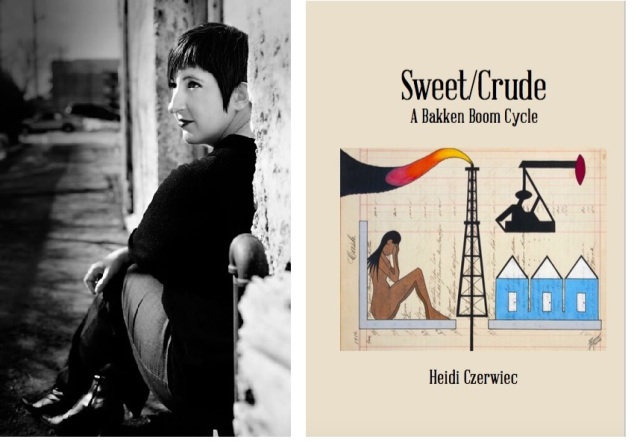

Sweet/Crude: A Bakken Boom Cycle (Gazing Grain Press, 2016)

Sweet/Crude: A Bakken Boom Cycle (Gazing Grain Press, 2016)

Who are some of the women who influenced your writing or you personally?

Betty Adcock is my poetry mom, the first person to take my writing seriously and encourage me when I was a teenager. Jacqueline Osherow and Moira Egan, who taught me everything I know about sonnets. The generous Allison Joseph, poetry’s biggest cheerleader, who taught me how to be part of a literary community, and Sharon Carson, who taught me how to be part of an academic community and retain my sanity and sense of humor. Nicole Walker, Maggie Nelson, Lee Ann Roripaugh, Jehanne Dubrow, and Jane Satterfield, all of whom showed me a pathway from poetry into lyric nonfiction. My personal writing community – the people I trust with early drafts of my work – Debra Monroe, Chelsea Rathburn, Jen Fitzgerald, and Katrina Vandenberg.

What does feminism look like in the mostly social conservative Midwest? In what ways does the Great Plains area challenge feminist ideology?

I guess I’m not sure how to answer this question, because the Midwest is a huge region with varying political stances and versions of feminism. North Dakota is incredibly conservative, but it also has the only Planned Parenthood serving women for hundreds of miles in three states that has fiercely defended its right to provide services – this speaks to both what feminism looks like and how it’s challenged. South Dakota is also conservative, but recently appointed Lee Ann Roripaugh – a mixed-race bisexual poet – as its state laureate. Some of the fiercest feminists I’ve met are from this region – maybe because they have to be? – but I’m grateful to know people like writers and activists Heid Erdrich and Debra Marquart, North Dakota’s DNC chairperson Kylie Oversen, and Nikki Berg Burin who worked tirelessly to help stop sex trafficking in the Bakken.

Beyond the sound of trains and the traffic they cause, personally, how did the boom affect your life between the time before the boom and when you left North Dakota?

When I first moved to North Dakota, people constantly defaulted to thinking I was in South Dakota, because no one believes people actually live here. I used to go camping out in Roosevelt National Park, back when the area had few visitors. Once the boom started and it caught the media’s attention, people seemed somewhat more aware that North Dakota existed – those who knew I taught there assumed that its citizens were rolling in oil money and cheap gas, but we really didn’t see either. I lived on the opposite side of the state, so we didn’t see the main influx of people and money, and the legislature was giving the oil companies huge tax breaks and cutting fines, so there was less money coming in than you’d believe. What revenues they raised went mostly to trying to manage the overwhelmed infrastructures (physical and social) of western ND, into a frozen fund that couldn’t be spent for five years (I can’t decide if this was wise or limiting) and, sadly, to expensive state lawsuits to fight same-sex marriage and access to abortion. The money helped forestall the recession hitting state governments by a couple of years, but then oil prices dropped and many oil companies stopped drilling – you need a lot of personnel for drilling, but not to manage existing wells. In the last few years before I left, the boom was going bust, the legislature had instilled large cuts targeting especially the university, and although UND is the liberal arts flagship, it was selling that out for money from the oil companies to its Mines & Engineering school.

What caused you to move away from North Dakota?

My husband took a job with a law firm in Minneapolis, and it opened up a lot of opportunities for our family.

Now that you have had time away from North Dakota, albeit in a nearby state, how do you feel about it?

I have mixed feelings. I’m glad I don’t live there any longer – I didn’t realize how little North Dakota provided for its citizens, even during the flush of the boom, until I moved away. I’m worried about what’s next for North Dakota after the boom – there were so few services in place before and during the boom, and with a budget crisis the state itself created through lack of taxing and regulating, there’s no safety net. What happens to all the families who moved to western North Dakota for jobs that no longer exist, but who can’t afford to move away? What’s going to happen to the girls and women trapped in sex trafficking when they’re not bringing in money to their captors? With little regulation before and no money to fund it now, what’s going to happen to the wastewater sites? It’s also weird to be among people, even nearby, who have little idea of what’s happening, though I’m grateful for the attention being brought by the Standing Rock Reservation water protectors and the tribes who have joined them in protesting the Dakota Access pipeline. Watching events escalate at Standing Rock from afar, involving people I’ve met, is so bizarre, and yet so inspiring. While the initial Bakken boom may be over, it’s still affecting residents. Regardless of whether that oil is transported, piped, or if a refinery is built on-site, these operations are occurring near major rivers and directly above the Ogallala aquifer, one of the largest freshwater repositories.

I do think it’s important to note that, when I wrote Sweet/Crude, it was as an observer to interrelated events facing North Dakota that needed to be witnessed. But now that these events have evolved to focus on how the oil industry is affecting indigenous communities, I feel the need to reframe Sweet/Crude as a sort of prologue or context to the current protest, but then get out of the way and refer current discussions to indigenous voices themselves.

So while I’m glad I’m no longer in North Dakota, I still feel an obligation to continue to monitor developments in the Bakken region.

In your chapbook, you talk about North Dakota as foreign, but not foreign. Could you explain that tension?

North Dakota is part of this country – a lot of the country looks to it for agriculture and now oil – and yet it’s last in the country’s imagination. It might as well have “here be dragons” printed over it on a map. The new tourism campaign starring hometown hero Josh Duhamel is titled “Legendary,” which belies the perception of the Great Plains as a place that existed in the past, in Western legend, but not real today. And people seem willing to allow horrible things to happen in and to ND, so long as the commodities flow. As long as North Dakota remains this foreign place that doesn’t seem quite real, we don’t have to worry about what our reliance on fossil fuels and agribusiness is doing to the people and the land and the water.

How much did you rely on Bill Caraher and Bret Weber’s research? What did that relationship look like while you wrote Sweet/Crude?

Bill, in particular, was a huge influence – aside from the data he collected about the mancamps, he developed his descriptions of the Bakken region into a project titled A Tourist’s Guide to the Bakken that was helpful. He and Bret were invaluable in navigating the Bakken safely, especially for me as a woman. Bill was also the instigator and main cheerleader for me as I wrote Sweet/Crude because it was important to him to have a multidisciplinary response to what was taking place in the Bakken, and he wanted my creative writing included in an scholarly anthology alongside work by archaeologists, sociologists, historians, social workers, and photographers that he compiled titled The Bakken Goes Boom.

In your chapbook, there is a sense of inevitability to these towns that have sprung up because of the oil boom becoming ghost towns. You use the phrase “we don’t need more ghost towns.” You mentioned that there have been two previous oil booms in North Dakota. Are there particular images, places, or events that inspired you to focus on ghost towns?

There’s a whole project titled Ghosts of North Dakota. Its creators – Troy Larson and Terry Hinnenkamp – have published a book, a website (ghostsofnorthdakota.com), and a Facebook page that all photodocument a visual record of the various abandoned places of the state. While many are the picturesque deteriorating remains of pioneer communities – decaying homesteads, barns, and churches – they’ve also documented structures built and abandoned by more recent economic events: the previous oil drilling boom in the ‘80s, and the military instillations and nuclear missile silos of the Cold War. Their work is fascinating, and was very much on my mind as I imagined what the apartment complexes – incomplete due to the sudden lack of demand – might look like in a decade or two.

You suggest in your interview with Gazing Grain Press’s Kate Partridge that “what lies beneath” the “North Dakota Nice” is xenophobia, suppression of women, mistreatment of Native Americans, and poor law enforcement and also that climate change affects all of us. When you ask “What lies beneath you?” are you asking that of the land and the people of North Dakota, or is the question also addressed to the reader? You stated that climate change’s exacerbation lies beneath all of us, but is there more that you want the reader to find beneath them?

As I said in that previous interview, “what lies beneath you” is intended both literally (landscape, oil, aquifer) and figuratively (history, social and racial tensions in the region), as well as suggesting the “lies” that underlie this boom – that drilling is sustainable, fracking is safe, natural gas is “clean,” no one lives in North Dakota so it’s not hurting anyone, it’s good for the economy (only in the most immediate and short-sighted ways). And while this phrase mostly addressed the land and people of North Dakota, it also addresses the reader to imagine what systems they’re part of or complicit in that contribute to social and environmental damage. The question is also directed at myself – to be an honest witness, I needed to examine my own involvement.

In your chapbook, you are indicting oil companies and “what lies beneath” them. Is there a further indictment of late capitalism in your work?

While the instigating event of the chapbook is the Bakken oil boom, it throws into relief other problems. I think the chapbook makes it clear that I’m also holding accountable agribusiness (with its unsustainable farming practices that rely on toxic fertilizers ironically made from petrochemicals), commodification of women’s and children’s bodies – anything for which we benefit at the expense of others’ suffering, especially when it occurs at a convenient remove.

Most of the transient workers in the Bakken are men. How did you approach writing about a very male dominated industry?

Mostly through research – I did travel to the region, but I didn’t feel very safe. I don’t know if that was due to reality, perception, or having all my research in the back of my mind. But being the only woman in spaces with hundreds of men is intimidating.

There is a sense of doom when talking about the problem with the area’s infrastructure, and how the State won’t invest in it. Are you critiquing the State’s reasoning, or revealing the ramifications of their decision?

It’s just a very bad situation with no good answer. If the State doesn’t invest in housing and human resources, the area becomes a very dangerous place without any safety nets, as we saw especially at the start of the boom: shantytowns that couldn’t withstand the winters, inadequate emergency services, traffic gridlocks, criminal opportunists. But if the State invests heavily in infrastructure, then those resources are ultimately wasted when there’s a bust or even when new drilling stops and companies require only a fraction of the staff for maintenance of existing wells. It’s difficult to find that balance. But North Dakota is a conservative state created with a “sodbuster” attitude, that only the tough survive, and the legislature rarely invests in social resources even when budgets are flush, so this boom did portend doom, in many ways.

Sweet/Crude is prose driven and lyrical, while also feeling academic. How important is it to balance abstract ideas with artistic excellence in writing? What do you want this balance to evoke in a reader?

Much of my work skirts the line between lyric and academic. I have an academic PhD, with a creative dissertation. I tend to write what I call documentary poetics – researched information on a nonfiction topic (Fifties pinup Bettie Page, a 19th-century Chinese youth with a parasitic twin, the origins of Chanel N° 5), but rendered lyrically, and often including the weird details considered irrelevant in scholarly research. I think it’s those weird and specific details that make abstract ideas like colonialism or gender politics or environmental impact into something human and moving – in this way, we return to Horace’s dictum that poetry should “instruct and delight.” I don’t necessarily agree that all poetry need do this, but when you are trying to teach or inform your reader, beautiful writing can make the lesson more palatable and memorable.

What projects are you working on now? How is your book, Real Mother, progressing?

At this point, the book manuscript for Real Mother is over halfway written, and I have several other parts of it sketched out. I’m also assembling another collection of essays called Fluid States that includes Sweet/Crude, among other pieces about perfume, canning tomatoes, being the subject of online outrage, and mushrooming.

*

Heidi Czerwiec is a poet and essayist and serves as Poetry Editor at North Dakota Quarterly. She is the author of two recent chapbooks — A Is For A-ké, The Chinese Monster, and Sweet/Crude: A Bakken Boom Cycle — and of the forthcoming collection Maternal Imagination with ELJ Publications, and the editor of North Dakota Is Everywhere: An Anthology of Contemporary North Dakota Poets. She lives in Minneapolis.

*