“I not only inherited these stories and traumas. They easily became my obsessions.”

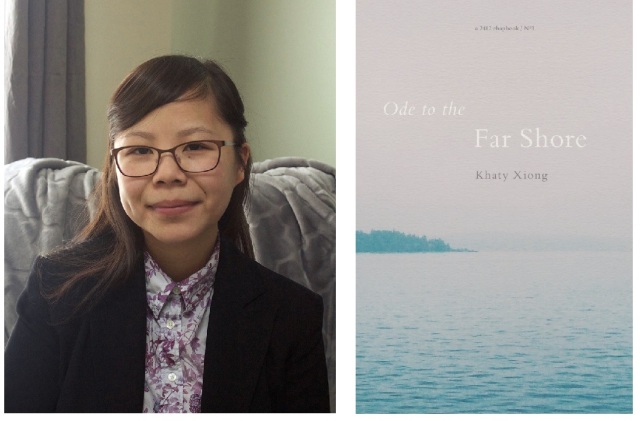

Ode to the Far Shore (Platypus Press, 2016)

Ode to the Far Shore (Platypus Press, 2016)

What obsessions led you to write your chapbook?

World mythology, legends, and folklore have long interested me since I was a child. In particular, Hmong mythology and origin stories have always fascinated me. I grew up hearing many of these stories surrounding how creatures came to be, which ones to fear and which ones to revere as gods and good spiritual forces. In the mix of these stories, my parents would often share with me what their lives were like before immigrating to the U.S.: the Secret War in Laos, hiding in the jungle to avoid persecution from Lao communist forces since my father, like many of my uncles and relatives, along with several thousands of Hmong and other ethnic tribes, aided the U.S. during the Vietnam War, and ultimately how my family and others had to cross the Mekong River in order to secure refuge in Thailand. Many died making this dangerous trek. My parents’ survival stories have long stayed with me; besides, they weren’t the only ones who talked about these experiences—after all, the Hmong’s presence in the U.S. is a direct result of the failed war, and so, Hmong people talked and longed all the time for “the old country.” The Hmong diaspora is my beginning. I not only inherited these stories and traumas. They easily became my obsessions that I have long been writing in my poetry.

What’s your chapbook about?

This chapbook is a response to the sudden loss of my mother, who passed away from a car accident in May 2016. After all the dangers that my mother faced as a young Hmong woman, surviving the war, immigrating to the U.S. and raising sixteen children and over twenty grandchildren, that my mother would be violently taken away by a car accident has been really traumatizing for me. I have been trying to understand the fate of my mother, how her car had split in two, how she remained intact despite the impact, how someone like my mother, who was also a shaman and medicine woman, a healer, could leave this realm the way she did—with so much hurt and unreconciliation. This micro chapbook is a window into my sorrow, love and good wishes to her spirit.

What’s the oldest piece in your chapbook? Or can you name one poem that catalyzed or inspired the rest of the chapbook? What do you remember about writing it?

The oldest piece is “Circadian,” which was actually written in response to the death of my oldest brother, who died in June 2014 from a rare lung cancer. I was still grieving his loss when one night I woke up with violent rustling in my left ear. Turns out a silverfish had crawled in there. It was not the first time an insect had wedged itself into my ear, so close and tender to my brain. And just like the last time this happened, of course, I panicked (which is totally an understatement). Eventually, I drowned it out. Although this poem was written during my first year of grieving for Kue, before my mother passed, when I decided to put this little book together, after my mother passed, I came back to this poem because I felt like it was a universal elegy to the dead in my family—those whose deaths and sacrifices made my parents’ life in the U.S. possible. Kue was about two weeks old when Long Tieng, the U.S. military base in Laos, had fallen to communist forces. That was the start of the Hmong diaspora. When arranging the poems in this chapbook, I realized then that this poem was not only grieving my brother’s fate, it was also grieving those whose lives were lost before his, and especially right now, the death of our mother. This poem was speaking to me from the past, present and future; I had no idea that when I wrote this poem, I would also be writing about my mother’s fate.

What has the editorial and production experience with the press who picked up your chapbook been like? To what degree did you collaborate on the cover image and design of your chapbook?

Platypus Press was very straightforward and gracious with the chapbook. They were incredibly receptive to the work and accepted the book as it was, for which I am grateful. There wasn’t a whole lot of collaboration on the design, since that was a set design for all chapbooks they have published in the past. As for the cover image, I did ask for a couple of options since the cover image was also chosen for me. While I was rather pleased with their editorial choices, I wanted to make sure that the image truly reflected the poems. Ultimately, I settled on an image that was their original choice anyway, so I’m glad I was able to “talk” them back into their original cover, which is beautiful. I am very pleased with the love and care at Platypus Press.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on putting together my second poetry manuscript that will essentially be a larger version of Ode to the Far Shore, touching on Hmong mythology, origin stories, and the recent deaths in my family. My first book, Poor Anima (Apogee Press, 2015), was very much a book of elegies too; there is no denying that this second manuscript will also have the same fate. My grieving period is far from over.

What advice would you offer to students interested in creative writing?

Hold fast to your obsessions, and be faithful.

*

Khaty Xiong was born to Hmong refugees from Laos and is the author of debut collection Poor Anima (Apogee Press, 2015), which is the first full-length collection of poetry published by a Hmong American woman in the United States. In 2016, she received an Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Award in recognition of her poetry. Xiong’s work has been featured in The New York Times and How Do I Begin?: A Hmong American Literary Anthology (Heyday, 2011), including the following websites, Poetry Society of America and Academy of American Poets, among others.

*