“Fall in love with your own language.”

Two-Headed Boy (Organic Weapon Arts, 2017)

Could you share with us a representative or pivotal poem (or excerpt) from your chapbook? Perhaps something that introduces the work of the chapbook, or that invites the reader into the world of the chapbook?

Anders’ Poem:

Polaroid

A loose flap of skin passes just below

his eye. Bruises ride the bridge of my nose.

The dark ropes of handprints grip

both our necks. Our fresh buzzcuts

lumpy with goose eggs. It’s easy to forget

we were trying to kill each other.

Or at least I was. But what I wonder now

is why our father shot the photo before

he bandaged the hole where the nail

went in, stuffed my raw mouth with gauze.

We stand side by side against the garage,

eyes focused just beyond the lens,

each pointing at what we did to the other.

Kai’s Poem:

Jesse James Days

If I called to you now. If I carried your name to the skateparks

and railroad temples of rust, would you come to me, brother,

wherever you are in your faded arrangements,

your growing away from the past? Would you lie with me here

in the shore-grass, watching the college boys paint

the gazebo, the endless advance and retreat of the sea?

I’m trying to imagine us back to our origins.

Skitching the Friday night dump truck in Moorhead,

shoplifting soft packs of Camel Lights,

kicking our boards through the rodeo crowds at the fair,

searching the beer tent for half-finished bottles of High Life,

for cigarette butts in the ashtrays, for lighters,

for dime bags and dollar bills left on the tables, for anything

other than home.

Why did you choose this poem (or excerpt)?

Anders: “Polaroid” is a good example of the “brotherly trouble” that writhes in this book. It seems like the most intimate relationships are also the most dangerous––not always physically, but to risk real intimacy we face real danger too. That’s part of what the book is about.

Kai: When I wrote “Jesse James Days” it was sort of a break through poem. I could feel a new energy in the lines. Anders and I were going through a tough spot in our relationship and I was trying to understand the violence we grew up around, how it shaped us, what history it stemmed from. There’s a certain posturing that happens between brothers, but I wanted this poem to speak openly, from the heart. What happened was a kind of love song, and I think it’s one of the most important things I’ve written. It created an opening for the rest of my poems in the book.

What’s your chapbook about?

Anders: Two-Headed Boy is about the explosive bonds between brothers, and sort of lets you in on a lifelong conversation that Kai and I are having with each other––from the years of intense fighting when we were little, to times when we were estranged, to times when we’ve traveled together on freight trains and slept in weird spots all over the country, utterly dependent on one another for sanity and companionship. In a larger sense, it’s about the danger of intimacy, the endurance of family, and the redemption and camaraderie of adventure.

Kai: The book is definitely a conversation between me and Anders, but it’s also a record of our lives. It charts the development of our relationship over time. We both write autobiographical poems, so the stories in the book represent a progression of two perspectives, reflecting each other, contradicting each other, creating a kind of collage of experience. I don’t know if this is as interesting to readers as it is to us, but a big part of the project is the travelogue element, the recording of where we’ve gone together, what our relationship has endured.

What obsessions led you to write your chapbook?

Anders: A deep love of adventure, the unbearable depths of intimacy between two people, a yearning to experience a tangible version of God, fear of isolation, recurring images in my mind and in my dreams, an urge to make something out of the transformative experiences I’ve had on the road, an urge to share the stories of perfect strangers who have saved my life, fear of forgetting, fear of chaos and a need to turn the chaos of my life into story and image and music.

Kai: I think the main obsession for me is experience. For years I’ve wanted to create a style of poetry that reflects a lived life, the empirical truth of the heart. When I was in my twenties I went through two mental breakdowns and it was difficult for me to read books. I was medicated for periods of time and struggled to find reasons to live. Every day I thought about burying myself in dirt, disappearing. I’ll talk openly about it now, but at the time it was more difficult to navigate. Therapy seemed like a joke and all the social mechanisms we use for dealing with depression just made me more depressed. Medication helped, but it also created a black hole of dependency. What saved my life was traveling and writing poems. Experiencing new things and writing about beauty. The kindness of strangers. The shifting hands of fate. When I would enter a mode of travel like this my brain would engage on a more intuitive level, and I would see poetic symmetry in things. I valued unique sensations and experiences because they kept me farthest away from the alternative, which had been living at my parents’ house taking anti-psychotics. Nothing else really helped me. The healing was found in novel experiences and poetry.

How did you decide on the arrangement and title of your chapbook?

Anders: Kai and I sent each other the poems we were considering for this project, and then we each helped choose the other’s poems. We knew we wanted to use a “call-and-response” format, so once we had all 18 poems, we just started ordering them, one by me, one by Kai, all the way through. That part was weirdly easy, although we did rearrange a few things after a first draft. The title comes from the band Neutral Milk Hotel, which has a song of the same title. The book’s epigraph is a lyric from that song: “I am listening to hear where you are.”

Kai: The poems have an image set dealing with dismemberment and displacement. Many of the scenes involve Midwestern landscapes and references to a violent past. There’s a “fingerless man” in a few of the poems. There are descriptions of hearing impairment and ears being shot off. The brothers in the poems are always on the move, in states of transition from one place to the next. The “Two-Headed Boy” title, apart from the Neutral Milk Hotel reference, is also a nod to the traveling circus, which used to go from town to town in the Midwest, often traveling by train.

Describe your writing practice or process for your chapbook. Do you have a favorite prompt or revision strategy? What is it?

Anders: I don’t have any big secrets. I just write everyday. I would recommend getting in touch with your body and your breath. And I’d memorize your poems after you draft them, so you can work on them in your head and focus on hearing the music and rhythm.

Kai: I need to be moving when I write. I can’t just wake up in my pajamas and start typing. I usually go for a run in the morning, pay a little visit to my coyote friend in the park, eat breakfast and play some guitar. Then I’ll get on my bike and take photos around the city. I’ll talk to strangers and see what people are saying, what the mood is. For me, writing poetry is about connecting with a spiritual rhythm. It’s a way of seeing and moving through the world.

What has the editorial and production experience with the press who picked up your chapbook been like? To what degree did you collaborate on the cover image and design of your chapbook?

Anders: Organic Weapon Arts has been so awesome to work with! Jamaal May did an absolutely immaculate job with the design––both cover and interior––and was generous enough to let Kai and I have a ton of input. (Thanks, Jamaal!) Tarfia Faizullah had a keen eye as editor––so keen that there’s not a single misplaced comma from cover to cover (Thanks, Tarfia!). And the contest judge, Laura Kasischke, wrote us the most generous blurb (Thanks, Laura!) Thanks to the OW! Arts team, the book is gorgeous! I’d highly recommend sending them your chapbook!

Kai: Jamaal and Tarfia have a super progressive view of what 21st century poetry can be, who the audience is, what we’re trying to accomplish as artists. I’ve admired their work for years and it’s inspiring to be able to work on this project with them. They’ve supported our vision completely and have been very encouraging about ways to develop and imagine the book. Honestly, they’ve felt more like family than book publishers.

If you have written more than one chapbook or novella, could you describe each of them in chronological order?

Mercy Songs (Diode Editions) is our other coauthored chapbook, and, like its title suggests, the focus is on song. It has lots of lyric portraits and elegies, and the themes are more kaleidoscopic than in Two-Headed Boy. The other project we’ve worked on together is a short film called, “Riding the Highline,” about one of our train trips across the country.

What are you working on now?

Anders: I’m working on finishing my first full-length collection of poems (almost finished!)

Kai: I’m doing edits on my first book of poems, RAIL, which is coming out with BOA Editions in Spring 2018. I’ve been working on this project for the last ten years, and I’m thrilled to be able to share it with the world.

What advice would you offer to students interested in creative writing?

Anders: Follow the natural impulses of your personality and imagination. Notice the ways you like to convey information or stories or jokes when you’re just talking with your friends or whatever. Are you more interested in the larger story, the details, or in what people say? Do you like tangents or straightforwardness? Those kinds of things will help you work on your craft. Also for craft, every time you don’t like a poem or a book or a movie, try to really understand why; then don’t do that. More toward content: record your dreams; notice what obsesses you when you daydream, what you’re ashamed of, what you do and don’t want to share. All this stuff is pretty much like getting to know yourself. And, like being a teenager, it’s about letting go of the notion that there are cool people somewhere doing cool stuff, and you should try to change to become more like that. Eventually you realize that your weird quirks are the good stuff, and the stuff that will ultimately shine through in your work––even though your quirks usually seem a little sloppy and wonky when you’re young, which is why they’re often destroyed in writing workshops. In the end, it’s about being yourself. But as a writer, you have to be yourself (on the page) long enough to figure out how to harness it.

Kai: I would say do your own thing. No matter what anybody tells you, be original and trust your voice. Fall in love with your own language. Don’t write poems you think you should write, write poems you need to read. There’s a big difference between these approaches. The first will get you published and win you awards, the second will make you a real poet. It will develop your soul. It will give you the strength to continue. Waste time. Allow yourself to fail. Become an artist before you become a critic of other people’s art. Remember that no one else can do this but you. If you follow your own vision, it will take a long time. You will spend a few years with no social or financial support. Your parents will worry about you. Your girlfriend/boyfriend will start to have doubts. Other writers will be jealous and condescending about your work. Editors will reject you because editors are not writers. They only see what they’ve seen before and mostly they’re just looking out for themselves. I know it sounds rough, but this country is not easy on writers, especially poets. It will be hard for a while. But if you make it through a few years and develop a practice, an original style, a community of like-minded writers, the reward is more valuable than anything else in the world.

*

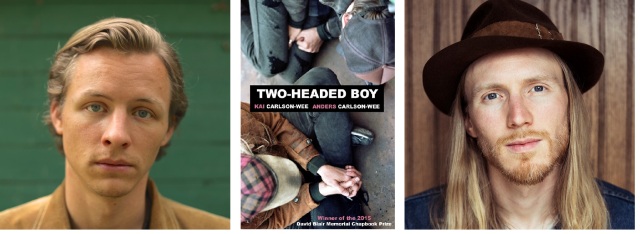

Anders Carlson-Wee is a 2015 NEA Creative Writing Fellow and the author of Dynamite, winner of the 2015 Frost Place Chapbook Prize. His work has appeared in Ploughshares, New England Review, Poetry Daily, Best New Poets, The Best American Nonrequired Reading, and Narrative Magazine, which featured him on its “30 Below 30” list of young writers to watch. Winner of Ninth Letter’s Poetry Award, Blue Mesa Review’s Poetry Prize, and New Delta Review’s Editors’ Choice Prize, he was runner-up for the 2016 Discovery/Boston Review Poetry Prize. He lives in Minneapolis, where he serves as a McKnight Foundation Creative Writing Fellow.

Kai Carlson-Wee is the author of RAIL (BOA, 2018). He has received fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and his work has appeared or is forthcoming in Ploughshares, Best New Poets, TriQuarterly, Blackbird, Gulf Coast, and The Missouri Review, which awarded him the 2013 Editor’s Prize. His photography has been featured in Narrative Magazine and his co-directed poetry film, Riding the Highline, received jury awards at the 2015 Napa Valley Film Festival and the 2016 Arizona International Film Festival. A former Wallace Stegner Fellow, he lives in San Francisco and is a lecturer at Stanford University.

*

Two-Headed Boy (chapbook), by Kai and Anders Carlson-Wee

Mercy Songs (chapbook), by Kai and Anders Carlson-Wee

Riding the Highline (short film), by Kai and Anders Carlson-Wee

Dynamite (chapbook), by Anders Carlson-Wee

RAIL (full-length book), by Kai Carlson-Wee

*