“Within a world of braided oppressions, language remains both a source of pain and promise.”

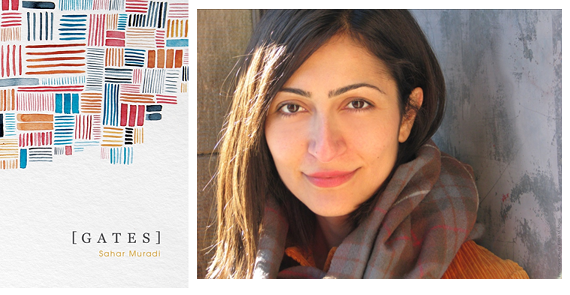

[ G A T E S ] (Black Lawrence Press, 2017)

Could you tell us a bit about your growing up and your path to becoming a writer?

I guess my path to writing started before me. In a mother who, as a young person, wrote stories and poems and buried herself in books, and in a father who would recite Hafez and Rumi with the ease of rattling off his own name. It was in the rupture of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan that would send my family fleeing to the U.S. and in all of the feelings and question marks after that would like landmines dot the entirety of my upbringing, which I discovered I could only near through poetry. It was in the swing-less playground of our apartment building in Queens, NY, where I was humiliated for not speaking English correctly and which put a kind of flame under me. It came in being uprooted constantly from rental home to rental home, from NY to Florida, so hungering for the stake of a word. It was in the championing of mentors like Mr. Bowen (teacher of algebra, not English!), who, in the eighth grade, handed me the collected works of Langston Hughes and asked me to keep a journal of my thoughts. By high school, I had three obsessions: R.E.M., thrift stores, and reading & writing. The last two remain.

How do you decorate your writing space?

My writing space is my journal, so that would mean wherever I am with my unruled pages—at my bedside, in a subway seat, at the airport gate. But my dedicated corporeal writing space is my desk at home, a small apartment I share with my partner. He is a minimalist, and I a thrift store whore, so you can imagine the battles waged. But my desk is mine, so it’s the one spot in our home that is highly populated, and by ephemera, ancestors, and amulets. A broad, long surface of Danish mid-century that can hold it all: a vintage Underwood typewriter from my landlady, a felt Kyrgyz shepherd with a spear of local driftwood from a neighbor, guinea fowl feathers in a bottle, a broken blue tile from my parents’ house in Kabul, my father as a young George Harrison (he passed last year), his handwritten Hafez poem to me for my MFA graduation, my grandfather framed in a karakul hat, my grandmother newly married in her teens, shelves of handmade journals and morning pages going back twenty years, an old floral tin “God Box” full of paper prayers, a small note that reads “I write to ease the passing of time,” a tall stack of current reads [in the pile: Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas and Amal Al-Jubouri’s Hagar Before the Occupation], and countless other solaces.

Could you share with us a poem from your chapbook? Perhaps one that introduces the work of the chapbook, or that invites the reader into the world of the chapbook?

[ ]

The one that belonged to her

The one where the light hit for the first time

The one between our houses

The one I crawled through to sleep on his chest

The one the dog squeezed through

The one at three over the candle and cake

The one at three at the checkpoint

The one between the earth and the sky, the refrigerator with wings

The one where he met us after one year and was a stranger

The one at the park, the one at Up Park, the one at Down Park

The one that pierced my face and they pointed and laughed

The one that took them away from me in a tube and sent them back to me tired

The one he went through, hairs shooting out

The one she went through, blood turning up

The one we all went through to get to the blinking lights with the cherries

The ones we put up when she was born

The ones we passed to leave for good

The ones we paid quarters to get through

The one they learned the names of Presidents for

The ones they needed social security numbers for

The one I touched in the dark of my room

The ones we couldn’t talk about, ever

The one we had to close behind us to stay in, to keep neat, to not be tempted

The one we tried to jump and failed

The one he jumped and wasn’t forgiven

The ones in the books that made animals of us

The ones that told us who we weren’t

The ones that hurt, that swung and cut and rattled long after they left

The ones that kept flowers

The one I went through to go north, to go abroad, to go east, to find my cardinal ways

The one she went through too tired to find her way

The one they have chosen to give them purpose

The different one I have chosen

The one I haven’t yet found

The one I am looking through now with the narrow slots and passages unseen

Why did you choose this poem?

This is the opening poem of the chapbook. I chose this poem because the title of the book comes from it. Originally, this poem was titled “Gates,” but none of the poems in the book have titles; they are preceded by a [ ], indicating a gate. It is the invocation, a kind of chant and invitation to pass through into the book. It reads very autobiographical, though it braids the personal and the social in a way that I think the rest of the book follows. It also reads summative, and that feels about right: as if I had to go through all of what I did to arrive at this point, this opening, this book, this—fill in the moment.

What obsessions led you to write your chapbook?

The panic that was my MFA. Not panic. I had largely a great experience at Brooklyn College. Most of the poems are from my thesis manuscript. That was a full-length book, but I’m not sure it worked well as one. However, as a chapbook, it does. At least Black Lawrence Press thought so!

What’s your chapbook about?

One of my professors used to say, “poems aren’t about anything.” We’d have long conversations about this. What qualifies a poem? How much is intention? Imagination? What is foreclosed by trying to say something vs. letting the poem dictate?

I’ll answer by speaking to the atmosphere they grew out of. Most of these poems were written between 2013-2016 and while I was in grad school. And that was a time of great experimentation for me. I tried on diction and tones and forms that felt new and strange and not “me.” So the poems have the twin flavor of mine/ not mine, and ultimately, I suppose, freed me of that concept. It was necessary to push against habit.

They also largely arise from a particular moment in time: when my father was diagnosed with terminal stomach cancer, when I married my partner, when we marked the 15th year of the US occupation of Afghanistan. Some pieces look back: at Guantanamo, at conflict in northern Mali, at travels. Most of them interrogate language in some way. So all of that is in the mix.

Here’s how I described it to my publisher:

[ G A T E S ] engages the themes and intersections of language, power, war, and illness. A poem, like a gate, may function as a passage—physical and literary—a threshold, a corridor, a barrier. The bracketing of the book title and the individual poems invokes the limitations of language to address individual and collective loss. The loss of a homeland meets the loss of a dying father meets the loss of meaning amidst war, racism, and environmental degradation. The work interrogates the contemporary moment’s collapsing of space, where the near and far, the private and global, are no longer distinct. Languages of politics and intimacy are in constant tension so that the violence of an occupied Afghanistan cannot, for example, be separated from the violence of the father’s cancer treatment. The poems ask, how is language a function of (in)justice? How is a life valued? Whose life? Whose poetry? Within a world of braided oppressions, language remains both a source of pain and promise.

What’s the oldest piece in your chapbook? Or can you name one poem that catalyzed or inspired the rest of the chapbook? What do you remember about writing it?

The oldest poem in the book is the one that begins “Kabul.” It was previously titled “A Secret Life in Misspelled Cities,” and was part of a project for dOCUMENTA (13), which included my friend and fellow poet Zohra Saed’s work, “The Secret Lives of Misspelled Cities,” and our personal photographs. The misspelling refers to the auto-correct function in Word that renders Afghan cities like Herat into Heart, or the historical and colonial spellings of such cities throughout time. My poem is based on my time living and working in Kabul from 2003-05. I was a young returnee to the country, and my experience there was very powerful, beautiful and traumatic. So much of my writing during that time and about that time has been fragmented. The fragment and the vignette are two forms that I often return to, and, I think, necessarily so given the content. Nothing feels complete, and saying a thing entirely is impossible, especially about a “homeland.”

How did you decide on the arrangement and title of your chapbook?

I loved this process. It was tortured and playful and something nearing divination. I was having a hard go of arranging them, when one of my professors, Ben Lerner, recommended that I “chop off the titles” and try rearranging them that way. So listening between poems without the hiccup of the title. I deleted the titles and then spread all the poems out on the floor of my apartment, which, thanks to my partner, was bare and neat. Then it was a bit of faith and a bit of Frogger, forward, backward, at the top, in the middle. Eventually, a kind of organic rhythm emerged. The poems actually worked better without the titles, so I lopped them off permanently. The table of contents is arranged by first line.

The progression in the chapbook goes a bit like: self, world, self in world and along the lines of faith/doubt in both.

Which poem is the “misfit” in your collection and why?

Well, because of the rogue time of grad school experimentation, several feel like misfits. But the two most egregious are, by first line, “We have lorded over nature,” and “Tell us about your violence and its relativism.” Both were written while listening to Democracy Now! I have an exercise, where I write while listening to the broadcast and draw language from the airwaves. But it’s not just language-culling, it’s also a way of engaging with the news that feels generative and not simply reactive. They are misfit in their wordplay and disregard for the lyric or “beauty” in a poem.

Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I suffer from acute perfectionism. It does not serve me or my poetry. I can noodle (as a colleague in copywriting once referred to my defect) a line until it’s lifeless. My favorite revision strategy is control-Z. To near the original spirit as much as possible. More often than not, it means letting go, or at least returning later and with fresher and kinder eyes.

What has the editorial and production experience with your press been like? To what degree did you collaborate on the cover image and design of your chapbook?

The first book I bought from Black Lawrence Press was Hala Alyan’s wonderful Four Cities. With my purchase, I received a lovely personal email from the press thanking me. Seeing how warm a place it was, I submitted to the open submissions not long after. So to my delight, I received a warm acceptance. And it has been nothing but loving since! Kit Frick, the Chapbook Editor, and Diane Goettel, the Executive Editor, have both been a dream to work with. They really take care of their authors, from how often and well they communicate to their care with each step toward production. And they’ve been tremendously patient with my revisions and the addition of a Notes section. It has been an incredibly smooth process so far.

Similarly, I truly lucked out with knocking on my friend Yolandi Oosthuizen’s door for help in coming up with a cover. She’s an amazing graphic artist who’s produced work for all kinds of media, but this was her first poetry book project. (Mine too!) She read the manuscript, after which she asked very thoughtful questions, and we had great email conversations leading to her making a mood board to consider imagery, textures, colors, font, and tone. From there, she presented several concepts, and several iterations of each—to serif or not to serif, for example—all of which I fell in love with, but ultimately chose this stunning watercolor she made. It has been one of the best parts of putting this chapbook together, both the collaboration and the exercise in thinking through the aesthetic elements.

What are you working on now?

I just finished a poem for a video project shot by my friend and artist Gazelle Samizay on Manzanar, one of ten Japanese American concentration camps in the US, and the histories and evocations of oppression in that landscape.

I have slowly been working on a prose piece about grieving my father’s death and the multiple deaths embedded within such a loss. I’m also writing (and sketching) a bit on toxic shame.

What question would you like to ask future writers featured at Speaking of Marvels?

How do you contend with saturation? The day’s news, flagged articles, the flagged books, the poetry tweets, the data the data the data. What’s your strategy to navigate your way home?

*

Sahar Muradi is a writer, performer, and educator born in Afghanistan and raised in the US / is author of the chapbook [ G A T E S ] / is co-editor, with Zohra Saed, of One Story, Thirty Stories: An Anthology of Contemporary Afghan American Literature / is a Kundiman Poetry Fellow and an AAWW Open City Fellow / has an MFA in poetry from Brooklyn College, an MPA in international development from NYU, and a BA in creative writing from Hampshire College / directs the poetry programs at City Lore / and dearly believes in the bottom of the rice pot. Author photo by Krista Fogle. Cover design by Yolandi Oosthuizen.