“‘Nola’ became a kind of magnet that attracted the earlier stories like iron filings. The missing girl was an absent center.”

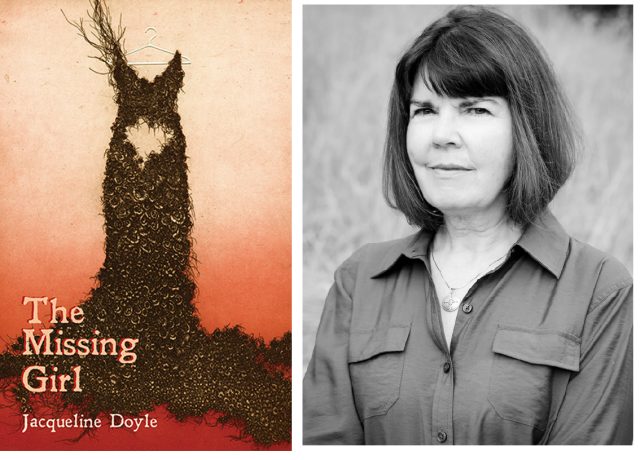

The Missing Girl (Black Lawrence Press, 2017)

Could you share with us a representative or pivotal piece from your chapbook? Perhaps something that introduces the work of the chapbook, or that invites the reader into the world of the chapbook?

Here’s an excerpt from the opening story:

You can see her in your mind’s eye, perky smile dimming, fear dawning in her eyes. Yes, you feel like you know this girl. Just the kind to go missing. Awkward and shy. Inexperienced and eager. Tender, playing brave. Dirt poor. You know. The kind of girl who’ll step right into your car if you call her pretty….

Jerrold Road is empty today. Birds gather in one of the tall, bare trees by the roadside, jabbering. Dead leaves whirl in the wake of a chilly gust of wind. Yellow grass. Gray sky. Not a car in sight. Just a girl in a gray sweatshirt, hood up against the cold, walking.

Slow way down and hit the button for the passenger window.

Go ahead, say it. “Hey pretty girl, want a lift?”

Why did you choose this excerpt?

It’s ominous, and the world of the book is dark. The nature of the narrator in the story, a copycat predator titillated by fantasies of another girl who’s gone missing, is not immediately clear. The reader sees this new girl, first walking on the road, then close up in the car, but the girl barely speaks. Her name is Early, but the story suggests it may be too late. There’s a lot the reader doesn’t know, which seems true of many of the other stories too.

What’s your chapbook about?

Girls who’ve been silenced or exploited or gone missing. Predators who’ve targeted girls. The effects of violence outside and inside of us.

What obsessions led you to write your chapbook?

Joyce Carol Oates said somewhere, “When people say there is too much violence in Oates, what they are saying is there is too much reality in life.” For a long while I was haunted by stories of abused or murdered or missing girls. The newspapers are filled with their stories, often consigned to the back pages, seemingly unremarked. Caite Dolan-Leach just published a fascinating article in Lit Hub (“Why Do We Love to Read About Missing Girls?” June 29, 2017) suggesting that missing girls have become a central cultural obsession, symptomatic of the systematic disempowerment and erasure of women in American society today, and reflected in many recent novels (including her own novel Dead Letters). It’s a disturbing reality that continues to obsess me.

What’s the oldest story in your chapbook? Or can you name one story that catalyzed or inspired the rest of the chapbook?

The stories were written over a period of four years, when I published many other flash on very different subjects, and I didn’t think of them as a group until later. They’re not arranged chronologically by composition, but in fact the oldest piece is also the first story in the collection, “The Missing Girl,” published in Vestal Review in 2013, and the last piece in the collection is also the newest: “Nola,” published in Monkeybicycle last year.

I was tremendously encouraged when J.T. Hill and the editors at Monkeybicycle nominated “Nola” for Best of the Net and a Pushcart, and when Ross McMeekin included “Nola” in his “Best Story I Read in a Lit Mag This Week” series on the Ploughshares blog. “Nola” became a kind of magnet that attracted the earlier stories like iron filings. The missing girl was an absent center, the way the dead woman that you can’t see in his painting becomes an absent but palpable center for the artist in Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio. She’s the “dark spot you might not notice,” the painter says, “the beginning of everything.” I was tempted to reword my epigraph from Anderson to make that clearer, but only Edgar Allan Poe (and maybe David Shields) can get away with altering and making up epigraphs.

What are some of your favorite chapbooks? Or what are some chapbooks that have influenced your writing?

Oh, so many! I wrote a piece (“Flash, Back: Revisiting Jayne Anne Phillips”) for the blog at SmokeLong Quarterly about my discovery that Jayne Anne Phillips’ Black Tickets started as a flash chapbook: Sweethearts (Truck Press). Her short prose influenced my writing (along with short prose by Joyce Carol Oates, Sandra Cisneros, Judith Ortiz Cofer, Dorothy Allison, Toni Morrison). Other chapbooks I’ve loved lately, in no particular order: Kara Vernor, Because I Wanted to Write You a Pop Song (Split Lip Press), Kathryn Kulpa, Girls on Film (Paper Nautilus), Stephanie Dickinson, Lust Series (Spuyten Duyvil), Daniel Riddle Rodriguez, Low Village (CutBank Press) and Low Village: Rules of the Game (Nomadic Press), Sarah Xerta, Juliet II (Nostrovia! Poetry), Laura S. Distelheim, We (Gold Line Press), Simone Muench, Trace (Black Lawrence Press). I know I’ve left some out (Carol Guess, Kristina Marie Darling, Peg Alford Pursell, Kelly Magee, others). Black Lawrence Press has some beautiful chapbooks.

What has the editorial and production experience with the press who picked up your chapbook been like? To what degree did you collaborate on the cover image and design of your chapbook?

I can’t say enough wonderful things about everyone at Black Lawrence Press—Diane Goettel, Amy Freels, and above all their chapbook editor, Kit Frick, who has devoted so much attention and care to this project. They’ve been wonderfully collaborative every step of the way (cover, design, editing), and run a very tight ship. Black Lawrence sponsors chapbook competitions every spring and fall and I urge everyone to enter. They’ve published some phenomenal writers. You won’t find a better press for your book.

What are you working on now?

Do-It-Yourself Night, a memoir-in-essays. Most of the essays have been published (two were Notables in Best American Essays). The most recent appeared in Superstition Review (Spring 2017) and The Gettysburg Review (Summer 2017). Creative nonfiction is probably my first love (it’s also the class I teach most often at Cal State East Bay), but flash is a close second.

Is there a question you wish you would have been asked about your chapbook? How would you answer it?

Do you write in more than one genre? If so, how does your writing in other genres differ? I write flash (fiction and nonfiction), creative nonfiction, fiction, and have even published the occasional poem. I often seem to reserve fiction for fun (after the labor of locating the truth, I love the freedom to make things up, to inhabit other characters), but I think my most intense and innovative writing has been creative nonfiction, a capacious genre with few hard and fast rules. Secrets emerge from hiding when I interrogate my life on the page. Silenced women repeatedly speak up in my hybrid nonfictions (Freud’s Dora, Mary Magdalene, Ariadne, fairy tale heroines, my great-grandmother, lost to history).

What advice would you offer to students interested in creative writing?

Never imagine that your first draft is your last draft, or that writing is easy, or that flash will be easier than longer stories. Notice everything. Read widely, outside your comfort zone. Be open to impressions and influences (someone “on whom nothing is lost,” as Henry James said). Accept that there will be setbacks. Don’t give up.

*

Jacqueline Doyle’s flash has appeared in Quarter After Eight, [PANK], Monkeybicycle, Sweet, The Café Irreal, Post Road, The Pinch, and Nothing to Declare: A Guide to the Flash Sequence (White Pine Press, 2016). She has published creative nonfiction in The Gettysburg Review, Southern Humanities Review, Catamaran Literary Reader, Superstition Review, South Dakota Review, and elsewhere. She lives with her husband and son in the San Francisco Bay Area, where she is a professor of English at California State University East Bay.

You sold me, I bought her book!

Thanks so much!

Pingback: Review: The Missing Girl by Jacqueline Doyle | The East Bay Review